Introduction

In recent years, the United Arab Emirates (“UAE”) has emerged as a recognized hub for technology and innovation. One of the pivotal drivers of this transformation has been the increase in venture capital (“VC”) activity in the UAE. VC is a form of private equity funding used as a viable alternative to traditional bank financing for new businesses.

VC investments are crucial in nurturing start-ups to scale their operations and promote innovation in key technologies. Although VC funds may well stimulate innovation and growth in the economy, the core mandate of these investment vehicles (like all others) is ultimately to produce satisfactory returns for its underlying investors.

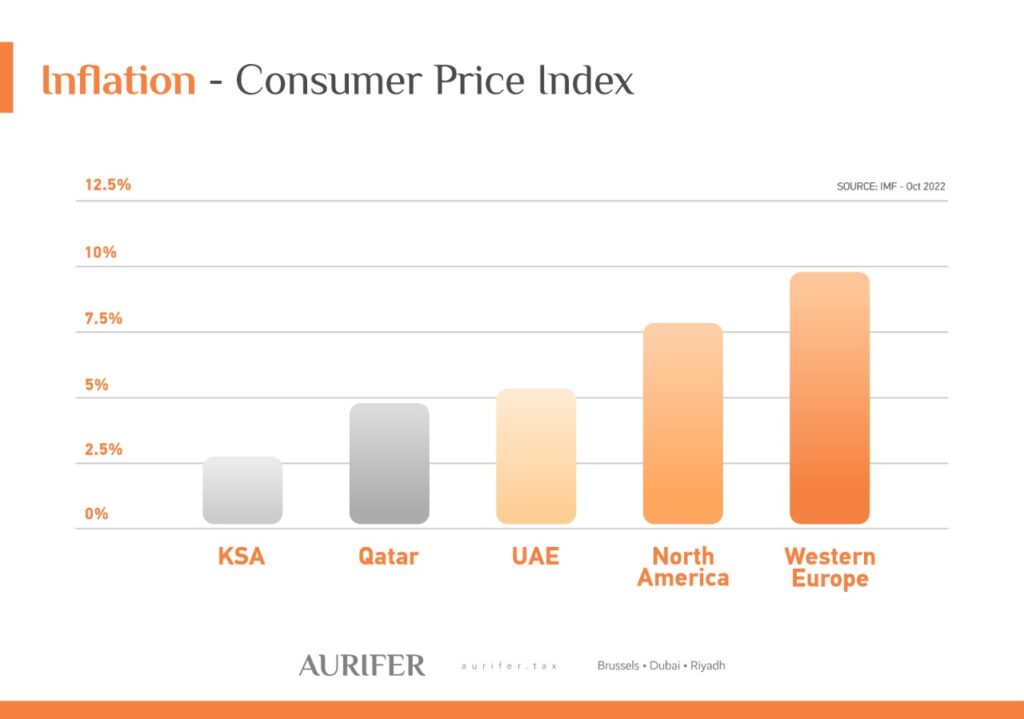

The recent introduction of corporate income tax (“CIT”) in the UAE may significantly impact persons involved in VC funds, both investors looking to deploy capital strategically and maximize returns and entrepreneurs seeking funding for the ‘next big thing’. Due to the international structure of modern investment strategies, it is also important that VC fund stakeholders are sufficiently aware of the international tax implications associated with their investments.

In this article, we discuss some of the nuances VC fund investors must consider going forward as part of the new UAE CIT and international tax landscape.

UAE CIT Law Overview

Broadly, the UAE Federal Corporate Tax Law (“UAE CIT Law”)[1] identifies two types of partnerships, namely:

- Incorporated Partnerships: these include limited liability partnerships (“LLP”), partnerships limited by shares, and other types of partnerships where none of the partners have unlimited liability, and

- Unincorporated Partnerships: these essentially involve a contractual relationship between two or more persons. The main feature of an unincorporated partnership is that the partners have unlimited liability for the debts and obligations of the unincorporated partnership and its business. Examples include general partnerships (“GP”) and joint ventures (“JV”). We have previously commented on applying this regime for law and professional services firms[2].

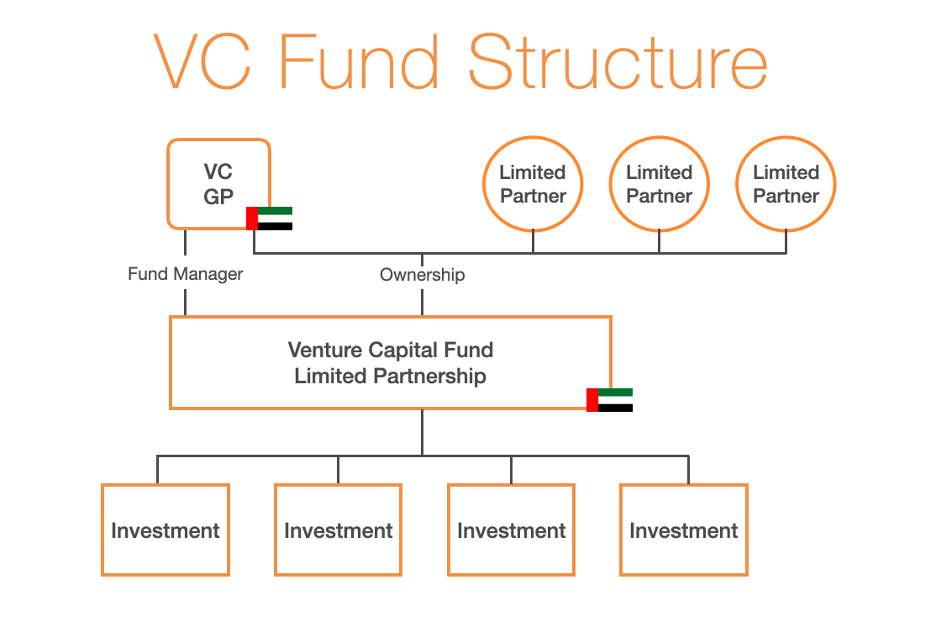

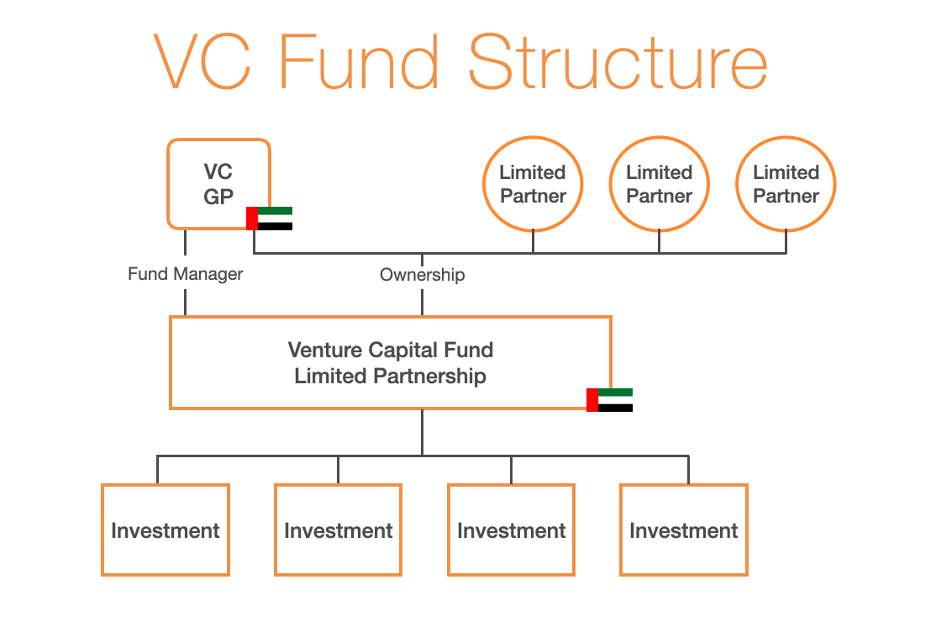

A VC fund is typically structured as a partnership, with a general partner responsible for managing the fund’s investments and limited partners providing the capital (the so-called classic GP-LP structure). Limited partners tend to be passive investors who have limited liability, while the general partner is actively involved in managing the fund. Below, we have included a diagram of the common VC fund structure.

Unincorporated Partnership and Fiscal Transparency

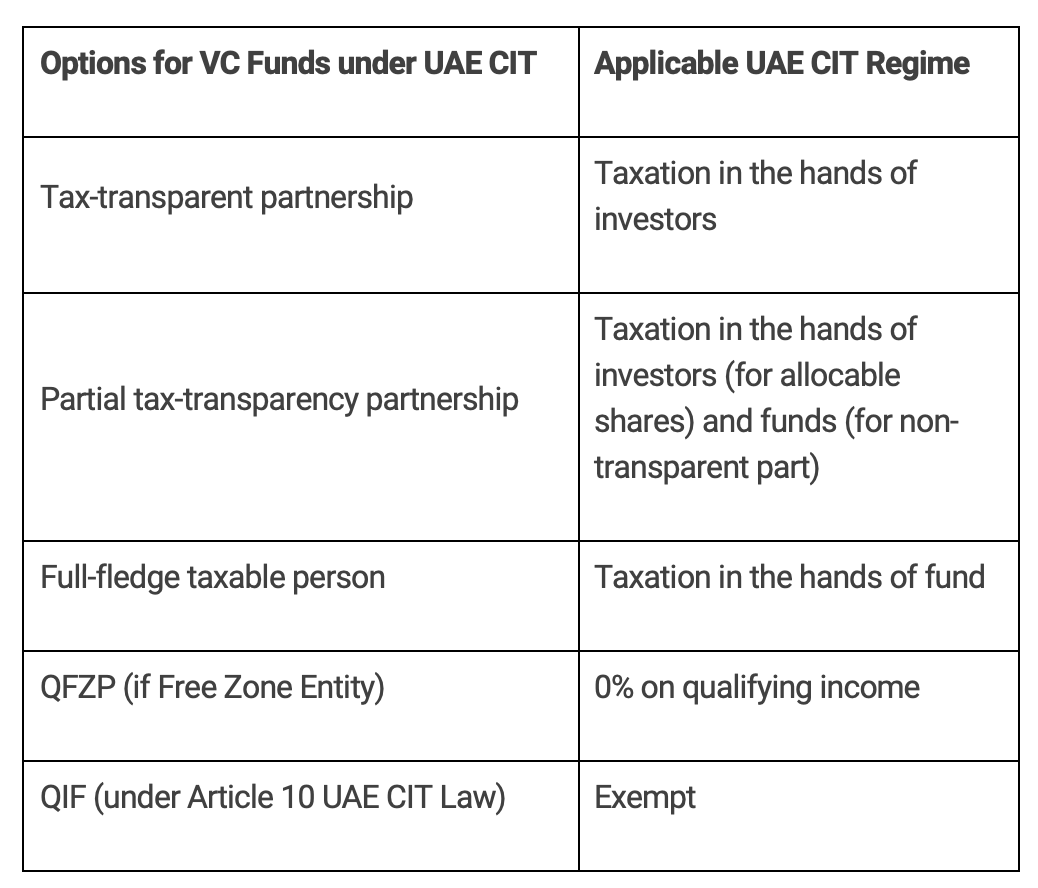

As discussed above, one of the primary considerations in characterizing a partnership for UAE CIT purposes is the concept of limited or unlimited liability. In this regard, an incorporated partnership where all partners have a limited liability is relatively straightforward from a UAE CIT perspective. Given the limited liability status of the partnership, it is considered to have a separate legal personality and taxable status, similar to a limited liability company or other juridical person. It is ultimately treated as a juridical person and taxed accordingly under the UAE CIT Law.

More complex is the UAE CIT treatment of unincorporated partnerships (which may involve an incorporated entity where partners have unlimited liability). A partner in an unincorporated partnership is regarded as conducting the partnership’s business as if it were his own, and he is jointly or severally liable for the obligations resulting from being in such arrangement.[3] For this reason, this type of partnership lacks independent legal personality[4] and is considered “transparent” for UAE CIT purposes.

According to Article 16 of the UAE CIT Law, any income derived by a tax-transparent vehicle shall be treated as earned by the underlying investor(s). In this regard, depending on the tax profile (natural persons vs. juridical persons) and tax residence status of the underlying investors, they may be subject to UAE CIT on the income derived from a tax-transparent entity. For example, a corporate investor in a UAE tax-transparent vehicle is subject to UAE CIT on the income to which that corporate investor is entitled. Conversely, a UAE tax resident natural person not conducting a business activity would not be subject to UAE CIT on their portion of the profit earned from the tax transparent entity, in so far as the activities of the unincorporated partnership do not bring a natural person within the scope of UAE CIT[5].

Each partner of an unincorporated partnership would need to assess whether they are within the scope of UAE CIT and, if so, register, prepare, and file annual UAE CIT returns accordingly, based on their portion of the income generated from the partnership. This causes important administrative obligations.

Another significant drawback of a transparent vehicle such as an unincorporated partnership is that they generally cannot claim any benefits under a double tax treaty (“DTT”) in so far as those vehicles do not meet the “liable to tax” criterion under Articles 1(2) and 4 of the OECD Model Tax Convention (“MTC”)[6].

As outlined above, VC structures typically have partners with both limited and unlimited liability. This potentially creates a so-called “partially tax-transparent entity” for UAE CIT purposes since the partnership is only considered transparent with respect to the income attributable to the partners with unlimited liability.

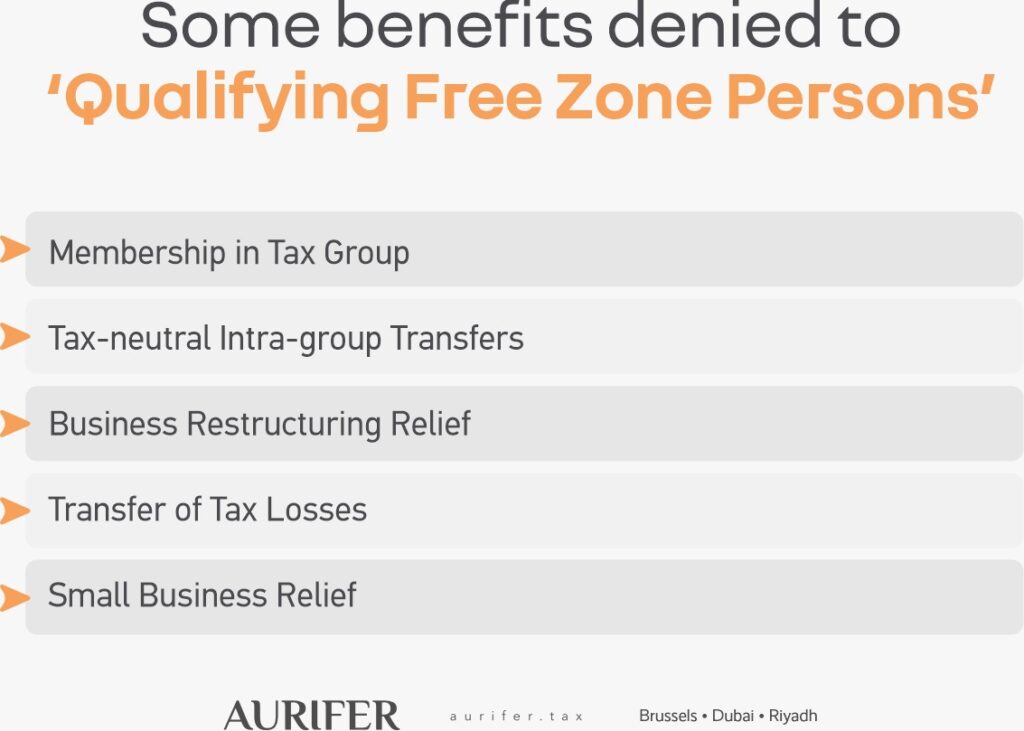

VC Funds and Taxable Person Election

To avoid some of the abovementioned administrative complexities associated with being a ‘transparent’ or ‘partially transparent’ investment vehicle, a VC fund may opt to be treated as a fully taxable person under the UAE CIT Law.[7] One of the benefits of this approach would be that the taxable person would be able to make a substantial claim to the application of rights under a DTT, given that it would be liable to tax. Additionally, this would reduce the compliance burden on individual partners, particularly where they are within the scope of the UAE CIT regime.

While, at first view, this option may seem inefficient from a tax perspective, as it would ensure the full partnership is within the scope of UAE CIT, several potential exemptions are available to a VC fund, as discussed below.

Qualifying Investment Fund

In the first instance, a VC fund may submit an application before the UAE Federal Tax Authority (“FTA”) to be considered exempt from UAE CIT as a Qualifying Investment Fund (“QIF”) where all of the following conditions are met:[8]

- The investment fund or the investment fund’s manager is subject to the regulatory oversight of a competent authority in the State, or a foreign competent authority recognized for the purposes of this Article.

- Interests in the investment fund are traded on a Recognized Stock Exchange, or are marketed and made available sufficiently widely to investors.

- The main or principal purpose of the investment fund is not to avoid CIT.

- Any other conditions as may be prescribed in a decision issued by Cabinet at the suggestion of the Minister.

As regards the fourth condition above, we note that a Cabinet Decision was issued[9] (no. 81 of 2023) containing other requirements to be considered a QIF, namely:

- The main business or business activities conducted by the investment fund are investment business activities, and any other business or business activities conducted by the investment fund are ancillary or incidental.

- A single investor and its related parties do not own the following:

– More than 30% of the ownership interests in the investment fund, where the investment fund has less than ten investors.

– More than 50% of the ownership interests in the investment fund, where the investment fund has ten or more investors. - The investment fund is managed or advised by an Investment Manager that has a minimum of three investment professionals.

- The investors shall not have control over the day-to-day management of the investment fund.

This exemption is likely to apply to many VC fund structures. However, some criteria (particularly the related party/ownership structure requirements from the Cabinet Decision) may be a potential tension point for certain funds.

Qualifying Free Zone Person

For those VC funds that may not meet the criteria for a QIF but are established in any of the UAE economic free zones (“FZs”), there is also the possibility to qualify for the 0% beneficial rate available to Qualifying Free Zone Persons (“QFZP”).

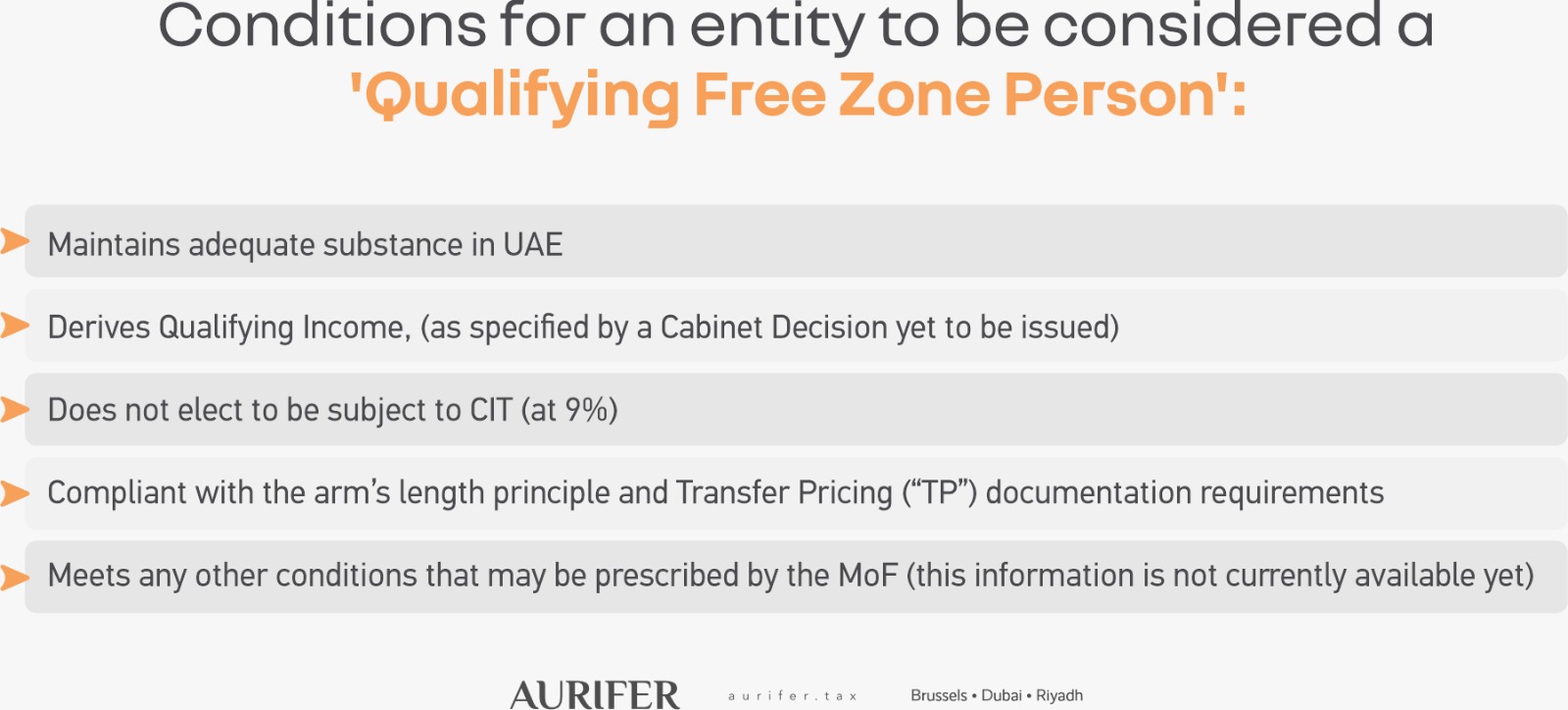

Given the continuing discussion regarding the QFZP regime and the prospect of upcoming modifications due to the public consultation on the UAE FZ CIT regime closed last August, we will only briefly summarize the key requirements below. Notably, a FZ person is considered a QFZP for UAE CIT purposes where it meets the following conditions[10]:

- It derives Qualifying Income.

- Its Non-Qualifying Income does not exceed the prescribed de-minimis requirements.

- It is compliant with the arm’s length principle and transfer pricing (“TP”) documentation requirements.

- It maintains adequate substance in the UAE.

- It does not elect to be subject to CIT (at 9%).

- It prepares and maintains audited financial statements.

Important in the context of VC funds is that the income generated from these vehicles will likely meet the definition of income derived from a “Qualifying Activity”[11] (i.e., it would be considered “Qualifying Income”). This is because the “Qualifying Activities” list includes, amongst others, the holding of shares and other securities.[12]

However, another important consideration and potentially critical point for a VC fund is that a QFZP must be a juridical person under the UAE CIT law.[13] Hence, the qualification for the QFZP regime depends on how the VC fund is structured, including assessing whether it has a separate legal personality for tax purposes.

International Tax Considerations

The UAE has more than 140 DTTs with partner jurisdictions[14]. This makes the UAE an appealing destination for VC funds to establish operations and engage in international investment opportunities. As such, it is also very important to consider the implications of the domestic tax treatment of a VC fund from an international tax perspective, particularly whether the VC fund can access benefits under a DTT.

A person can only claim treaty benefits under a DTT when he resides in one of the two Contracting States. One of the key criteria under Article 4 of the OECD MTC for tax residence is that the person is “liable to tax” in the Contracting State. We mentioned previously that a tax-transparent partnership is typically not eligible to claim treaty relief due to non-fulfillment of the “liable to tax” criteria.

For partially or fully tax-transparent entities, it is possible that the underlying investors may be considered tax residents in the UAE (provided they meet the relevant conditions in the DTT) and, therefore, be entitled to treaty benefits. However, tax treaty residence eligibility is subject to complex assessments for the VC fund and its investors.

The difficulty in accessing treaty benefits for tax-transparent entities is one of the key reasons a VC fund may elect to be a taxable person under the UAE CIT Law. However, there is also an argument that a QIF or QFZP would not meet the “liable to tax criteria”. The OECD Commentary on the MTC effectively leaves the interpretation of whether an entity satisfies the “liable to tax” criterion at the discretion of the source jurisdiction.

From our experience, ZATCA in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (“KSA”) has historically sometimes rejected claims by UAE FZ entities under the KSA-UAE DTT because they are not liable to tax in the UAE and, therefore, do not meet the residency criteria. Where the VC fund is not considered resident in the UAE, it could result in foreign withholding tax being applied on the payments received at gross, with no domestic credit available, as the VC fund is exempt from UAE CIT or is subject to tax at 0%.

Nevertheless, it is important to consider each DTT and transaction or arrangement on a standalone basis, as in some jurisdictions, a person is considered liable to comprehensive taxation even if the Contracting State does not actually levy any income tax.[15] As such, there may be scenarios where a VC fund can elect to be considered a taxable person and qualify as either a QIF or QFZP such that there is no domestic UAE CIT while maintaining access to treaty benefits.

Conclusions

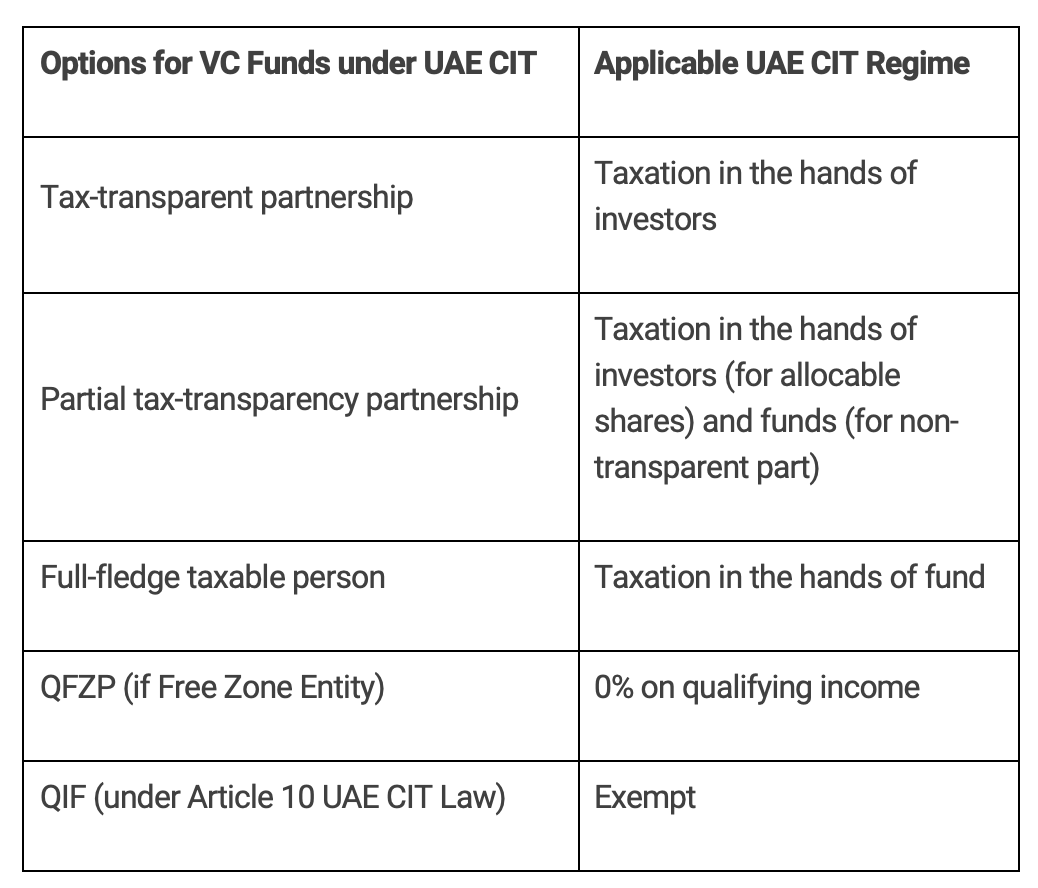

This article has outlined some potential intricacies that VC funds must consider when determining their “winning formula” under UAE CIT Law. This decision requires a critical evaluation by VC funds of the different options available (transparent vs. opaque, QIF, QFZP, etc.). VC funds must also evaluate the extent of their international portfolio, as well as the tax profile and residency of underlying investors, if they want to continue maximizing investor returns in the changing world of taxation in the UAE.

Summary Table

==

[END NOTES]

[1] Federal Decree Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses (“UAE CIT Law”).

[2] T. Vanhee, “Impact of UAE Corporate Tax on Law Firms and Professional Services Firms“, https://aurifer.tax/uae-corporate-tax-which-impact-on-law-and-professional-services-firms/, accessed on 2 October 2023.

[3] Article 16(9), UAE CIT Law; Clause 8.2, Corporate Tax General Guide issued on 11 September 2023.

[4] Clause 8.2, Corporate Tax General Guide issued on 11 September 2023.

[5] This is determined by Article 11(6), UAE CIT Law, for which the UAE Federal Cabinet issued Cabinet Decision No. (49) of 2023 On Specifying the Categories of Businesses or Business Activities Conducted by a Resident or Non-Resident Natural Person that are Subject to Corporate Tax. This Cabinet Decision determines that for resident and non-resident natural persons, wages, personal investment income, and real estate investment income are not subject to UAE CIT. For more details on the application of UAE CIT to natural persons, please refer to our previous articles: T. VANHEE, “Tax Implications for Resident and Foreign Investors in the UAE Real Estate”, https://aurifer.tax/tax-implications-for-resident-and-foreign-investors-in-the-uae-real-estate/, accessed on 2 October 2023; T. VANHEE., “CIT in the UAE: The PE Clause for Individuals”, https://aurifer.tax/cit-in-the-uae-the-pe-clause-for-individuals/, accessed on 2 October 2023.

[6] See Paragraph 8.3., OECD Commentary to the OECD Model Tax Convention (“MTC”) on Article 4, which states the following: “Where a State disregards a partnership for tax purposes and treats it as fiscally transparent, taxing the partners on their share of the partnership income, the partnership itself is not liable to tax and may not, therefore, be considered to be a resident of that State”. This reflects the idea of when a person is covered and is entitled to the benefit of a double tax convention (“DTT”) as specified in Article 1(2) of the OECD MTC (as updated in 2017) as regards wholly or partly transparent entities. Some treaties will, however, specifically note that a partnership is a resident. See Article 4(1)(b) of the DTT between the United States and Luxembourg or Article 4(1) of the DTT between Belgium and Luxembourg

[7] Article 16(8), UAE CIT Law.

[8] Article 10(1), UAE CIT Law.

[9] Cabinet Decision No. 81 of 2023 On Conditions for Qualifying Investment Funds for the Purposes of Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses.

[10] For more details on the QFZP regime, see L. Purcell, “To Qualify or not to Qualify: Analysis and Tax Advisory on the UAE Free Zone Regime, Interaction with Pillar Two, and Beyond”, https://aurifer.tax/to-qualify-or-not-to-qualify-that-is-the-question-the-uae-free-zone-regime-interaction-with-pillar-two-and-beyond/, accessed on 2 October 2023. See also UAE Corporate Tax on Qualifying Free Zone Persons, https://youtu.be/HmjnOAUFm7g, accessed on 2 October 2023.

[11] Ministerial Decision No. 139 of 2023 Regarding Qualifying Activities and Excluded Activities for the Purposes of Federal Decree Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses.

[12] Article 2(1)(c), Ministerial Decision No. 139 of 2023. It should be noted, however, that both management services and wealth and investment management services must be subject to the regulatory oversight of the competent authority in the State.

[13] Article 11(3)(a), UAE CIT Law.

[14] UAE Ministry of Finance (MoF), “Avoidance of Double Taxation Agreements” https://mof.gov.ae/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Avoidance-of-Double-Taxation-Agreements1.pdf, accessed on 2 October 2023.

[15] Paragraph 8.6, OECD Commentary to the OECD MTC on Article 4.