Impact of UAE Corporate Tax on Law Firms and Professional Services Firms

1. Application of CIT to revenue of law firms and professional services firms

Applying the new UAE Corporate Income Tax (CIT) to law and professional services firms can be complex. This is, mainly, because the underlying structures of legal and professional firms may also be complex. In this section, we will first discuss firms structured as a regular legal person, such as a Limited Liability Company (LLC). We will distinguish between UAE mainland LLCs and Free Zone (FZ) LLCs. Subsequently, we will discuss entities potentially treated as transparent under UAE CIT, together with UAE branches of foreign (non-UAE) companies.

a. Legal Structures

i. Firm structured as a regular mainland UAE LLC

This type of corporate structure will frequently be adopted by several UAE law firms. UAE law firms have rights of hearing, therefore, they are necessarily owned by UAE (or GCC) nationals. Generally, they have no legal reason to be established in a UAE FZ and can, therefore, mostly be found in UAE “mainland” (i.e., non-FZ).

If so, UAE LLCs will be subject to 9% CIT on their worldwide profits, adjusted for tax purposes according to the relevant CIT legislation. This will be the default position for any law firms which are organized through a Limited Liability Corporation (“LLC”) in the UAE mainland.

ii. Firm structured as a mainland UAE partnership

An alternative legal structure may be that of a partnership. To this end, the UAE CIT law distinguishes incorporated and unincorporated partnerships.

The FAQs published by the UAE Ministry of Finance (MoF) provide examples of incorporated partnerships. According to the MoF’s FAQs, incorporated partnerships include Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs), partnerships limited by shares, and other types of partnerships where none of the partners has unlimited liability for the partnership’s obligations or other partners’ actions[1].

This reference suggests that, where there is unlimited liability for corporate law purposes, the entity must be treated as transparent for CIT purposes[2]. This UAE approach is in line with that followed by other jurisdictions. Seemingly, incorporated partnerships where no partners have unlimited liability are subject to UAE CIT at the standard rate.

Unincorporated partnerships are described under the UAE CIT law as “a relationship established by contract between two Persons or more, such as a partnership or trust or any other similar association of Persons”[3].

Unincorporated partnerships are not considered taxable persons in their own right. Instead, they are considered “transparent”. It follows from this that partners rather than unincorporated partnerships are liable to tax, so that those transparent vehicles generally cannot claim any benefits under double tax treaties (DTTs), given that they do not meet the liable-to-tax criterion under Articles 1(2) and 4 of the OECD Model Tax Convention (MTC)[4].

The UAE Commercial Companies (CC) law, which is applicable in the UAE mainland and in any Free Zone not regulating corporate law itself, refers to two types of partnerships, i.e., a Joint Liability Company (JLC) and a Limited Partnership Company (LPC)[5].

Under the UAE CC law, a JLC is a company consisting of two or more physical partners who are severally and jointly liable in all their personal assets for the entity’s obligations[6]. As such, JLC would likely be treated as a transparent entity for corporate law purposes. Joint partners of a JLC are considered traders, and they are deemed to be conducting commercial activities directly.

Under the UAE CC law, an LPC is defined as “(…) a Company which consists of one or more joint partners, having the capacity of traders, who shall be liable, severally and jointly, for the partnership’s obligations, and one or more silent partners who shall not be liable for the partnership’s obligations, except to the extent of their contribution to the partnership’s capital. Silent partners shall not have the capacity of trader.”[7]

Given the criterion of “unlimited liability”, which the UAE seems to apply to both types of partnerships, JLC and LPC are likely to be treated as transparent for UAE CIT purposes, despite both being endowed with legal personality. This means that the individual partners will be considered as directly conducting the business, therefore being taxable persons of their own right liable to UAE CIT[8].

If transparency is not a preferred option, the legal entity treated as a partnership can file an application (i.e., an election) to be considered non-transparent (i.e., “opaque”)[9]. Where the application is successful, the status is effective from the start of the tax period in which the application is submitted or since the beginning of a subsequent tax period[10].

The election by an unincorporated partnership for non-transparency treatment under UAE CIT law is irrevocable, unless exceptional circumstances occur and subject to approval by the Federal Tax Authority (FTA)[11]. The unincorporated partnership, presumably only when transparent (since, otherwise, if opaque, the partners are disregarded for UAE CIT purposes), is required to notify the FTA within 20 business days from any partner joining or leaving its organization[12].

The underlying rationale behind an application for an incorporated partnership to be treated as an opaque structure and, therefore, as a full-fledged taxable person under UAE CIT could be:

- Relieving the partners from the tax compliance burden and achieving simplicity

- Enabling the partnership itself to access any of the 137 DTTs concluded by the UAE

iii. Mainland UAE branch of a foreign LLC

Sometimes, foreign firms are organized by way of a branch in the UAE mainland. The carrying out of professional activities through a branch in the UAE does not just have regulatory advantages in terms of the setup of the branch, but, when taxed, may also have the advantage that the branch (i.e., permanent establishment) income may be exempt or excluded from the scope of corporate tax in the country of the head office’s residence (in particular, in case of countries using the exemption method to avoid international double taxation).

There are no specific rules applicable to UAE mainland branches of a foreign LLC. Their profits are, therefore, taxable at the standard UAE CIT rate of 9%.

Complications with UAE-established branches, however, may arise with the allocation of profits between head office and branches, which requires a careful transfer pricing analysis of the functions, assets, and risks, following the OECD’s recommended Separate Entity Approach[13].

The discussions around profit allocations to branches could lead to mismatches between the UAE and the other country concerned, potentially leading to international double or non-taxation of the same profits. It is, therefore, critical for legal and professional firms operating cross-border to seek confirmation with the tax authority on the taxation of their branches, as well as about the method to avoid double taxation in the country of residence (i.e., the country of the head office or first establishment).

iv. Mainland UAE branch of a foreign partnership

It is common that law (mostly) and professional services firms (less so) outside the UAE and GCC region are organized by way of a partnership or LLP. This is very common in some countries like the United Kingdom and the United States.

The partnership structure offers a number of benefits in terms of the flexibility of making partners entitled to profits, but also regulatory, administrative and legal ease of having partners enter and exit, as well as other elements such as profit share entitlement for partners. A partnership is usually treated as transparent for corporate tax purposes in the country of residence or first establishment. It follows that only partners are subject to tax, usually by levying a Personal Income Tax (PIT) on their profit share entitlement.

If available, these partnerships may prefer setting up branches abroad, in countries which consider the branches and their partnerships as tax-transparent. Tax transparency in a foreign country gives the partnership more leeway on concluding cross-border ventures, sweeping up all income and expenses into one pool, determining a bigger profit pool to then subsequently distribute profits to the partners based on their profits share entitlement.

The circumstance that a partnership operates abroad in a jurisdiction where the partnership is not treated as tax-transparent may potentially create what is called, in technical terms, a “source-residence conflict”[14]. Taxation in the country of source cannot be considered in the country of residence if the foreign partnership would not be liable to tax itself in its residence country in the first place.

Whether the country of residence would generally provide an exemption or a credit is irrelevant: in this instance, the taxes paid in the country of source can be regarded only as a business cost for the partnership. Some countries solve this international tax issue through a legal fiction, which consists of allowing the partners to claim the tax credit which would have accrued to the partnership, had it not been transparent.

For this reason, it is often beneficial to set up a full-fledged subsidiary in those countries where the local branch would not be considered tax-transparent and may have an alternative structure catering for the countries where partnerships are not tax-transparent.

The UAE has provided flexibility in the application of its CIT to UAE branches of foreign unincorporated partnerships. The treatment of foreign partnerships under UAE CIT aims to mirror the tax treatment in the country of residence of the unincorporated partnership. If the partnership in the country of residence is tax-transparent, then the UAE would allow the same tax-transparent treatment for the UAE branch of the foreign partnership.[15] This is also the most common approach followed by other jurisdictions[16].

If the foreign partnership is treated as tax opaque in the jurisdiction of first establishment, then the UAE will not consider the UAE branch as transparent and levy UAE CIT upon it accordingly. The UAE CIT treatment will then be the same as the one applicable to a foreign LLC which has a branch in the UAE.

The tax transparency of UAE branches comes with some conditions attached:

- The foreign partnership is not subject to tax under the laws of the foreign jurisdiction, i.e., if it is subject to tax, it is not transparent[17].

- Each partner is individually subject to tax with regard to their distributive shares of any income in the foreign partnership[18].

- The foreign partnership submits an annual declaration to the FTA confirming it meets the above conditions[19].

- Adequate arrangements exist for cooperation between the UAE and the jurisdiction under whose applicable laws the foreign partnership was established for the purpose of exchanging tax information on the partners in the foreign partnership[20].

We discuss each of these conditions further below.

– Foreign partnerships not subject to tax

The complication around the application of the conditions laid down above is not so much on the requirement relating to the tax transparency of the foreign partnership. This is a condition which should be met, for example, in the case of a UK and US LLP. For partnerships established in other locations, an analysis will need to be made of the actual tax treatment of a partnership there.

– Each partner is individually subject to tax

The second condition, in comparison with the former one, is less straightforward. Tax transparency assumes taxation is triggered at another level, i.e., at the partners’ level. In the case of a UK LLP, partners in the LLP pay PIT to the extent they receive the income as self-employed partners.

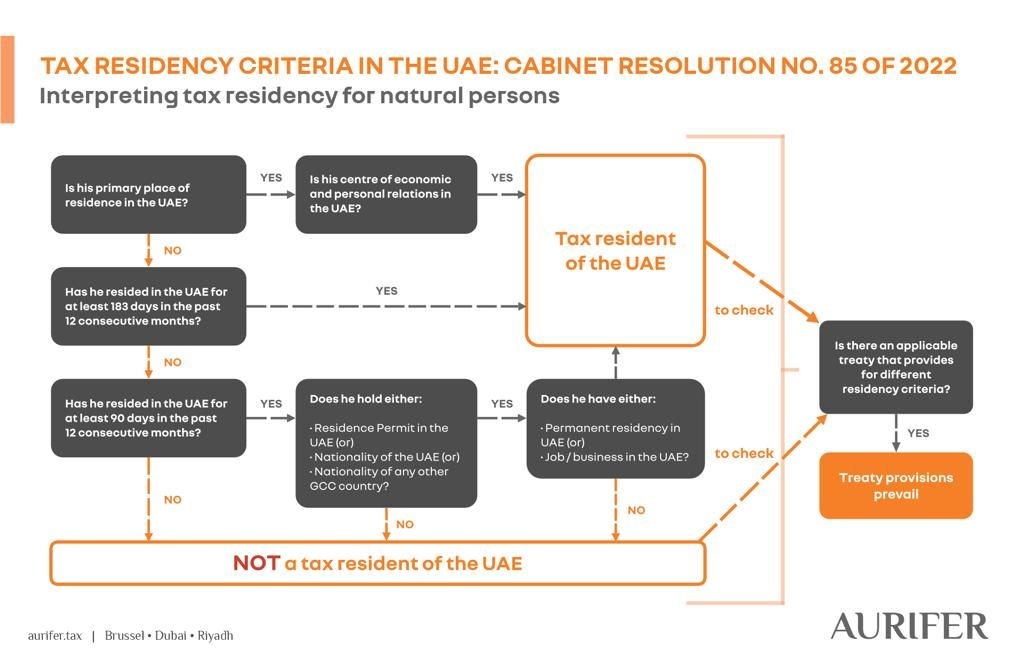

It should be noted that natural persons, when conducting a business, are also in the scope of UAE CIT[21], and, for UAE CIT purposes, “Business” is defined in the same way as it is in the VAT law[22].

As regards resident natural persons, earning wages cannot be considered as conducting a business, regardless of the wages earned[23]. A wage is defined as “The wage that is given to the employee in consideration of their services under the employment contract, whether in cash or in kind, payable annually, monthly, weekly, daily, hourly, or by piece-meal, and includes all allowances, and bonuses in addition to any other benefits provided for, in the employment contract or in accordance with the applicable legislation in the State” (emphasis added).

In the UAE, partners working in a local branch of a foreign LLP would generally have an employment contract. Without an employment contract, historically, foreign partners could not obtain residency in the UAE, given that they require a visa. Their employment contract dictates their remuneration, which generally consists of salaried income plus a (more rather than less) substantial bonus at the discretion of the law or professional services firm.

This implies that the requirement to be subject to tax for the partners in order to obtain transparency may conflict with their (non-tax) employment status. Therefore, the actual employment relations between the partners and the firm need to be thoroughly analyzed.

If the UAE resident partners are not to be treated as independent or self-employed, and therefore conducting a business for UAE CIT purposes, the UAE mainland branch would be considered taxable, thus creating a “source-residence conflict”, potentially leading to a higher tax burden for the partnership[24].

When it comes to UAE-resident partners who earn salaried income and are entitled to a profits share, the subject-to-tax condition may not be met. A remedy against it could be to provide equity partners with an employment contract with a nominal salary (e.g., “nummo uno” or AED 1), stating that this salary constitutes an advance on their profits share, and reclaim the nominal salary when their profits share is paid out.

When it comes to foreign (non-UAE resident) partners in the partnership, the partner is considered subject to tax if they would be subject to tax on their distributive share of any income from the partnership in his (i.e., that partner’s) country of residence[25].

– Submission of annual declaration

The form and manner for this compliance requirement are yet to be defined by the FTA.

– Tax information exchange agreement

It is unclear what the MoF is actually referring to with this condition. There is a wide variety of international agreements which countries enter into for the purposes of exchanging tax information.

If, with this condition, the MoF is referring to the equivalent of Article 26 of the OECD MTC, then the fact that the UAE does not have a DTT with all countries (the United States being a notable absentee in this regard) may prevent the application of tax transparency treatment of a foreign partnership.

However, other tax agreements may also regulate the exchange of financial information, which may eventually be used for UAE CIT purposes. This is the case of FATCA, which requires banks and other financial institutions in the UAE to exchange information on account holders with the United States[26].

v. Firm structured as a UAE FZ LLC or non-transparent entity

The first question which needs to be asked is whether the FZ-established firm is transparent for tax purposes. The Company Regulations for the specific FZ will need to be analyzed to understand whether any of the partners have unlimited liability. In those FZs, different regimes may apply. For example, the DIFC has a separate limited partnership regime[27], and so does the ADGM[28]. These regimes need to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.

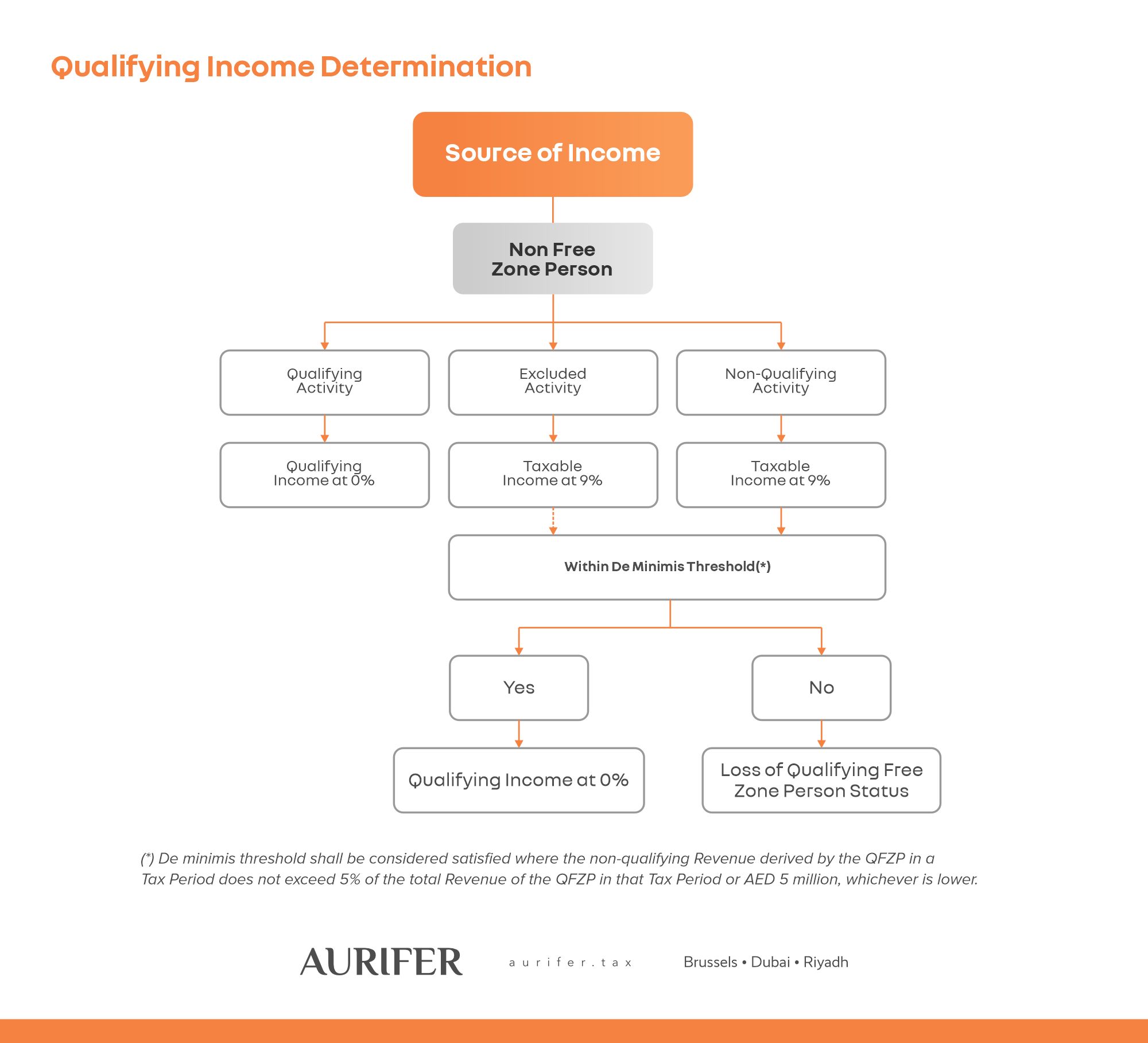

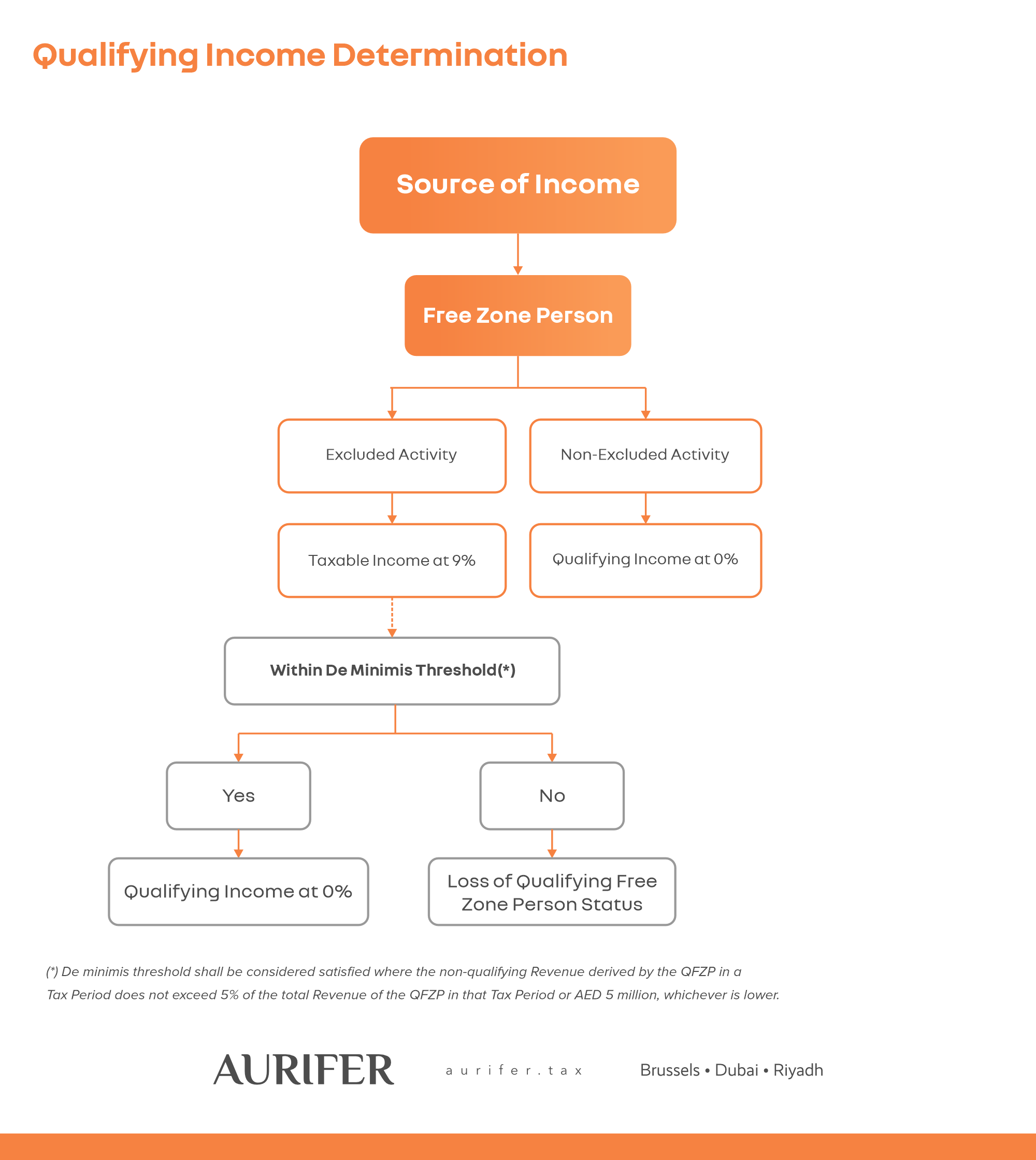

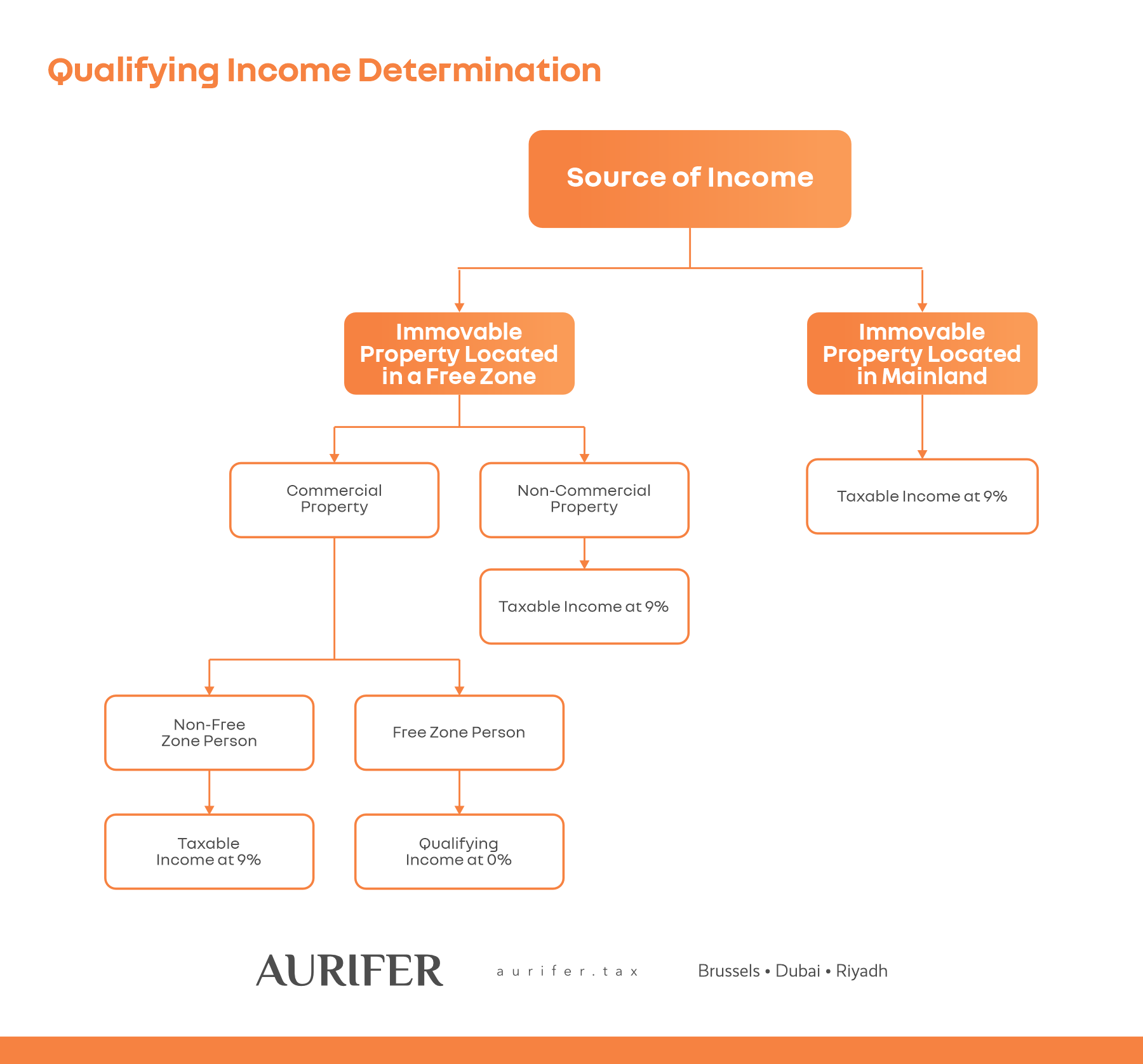

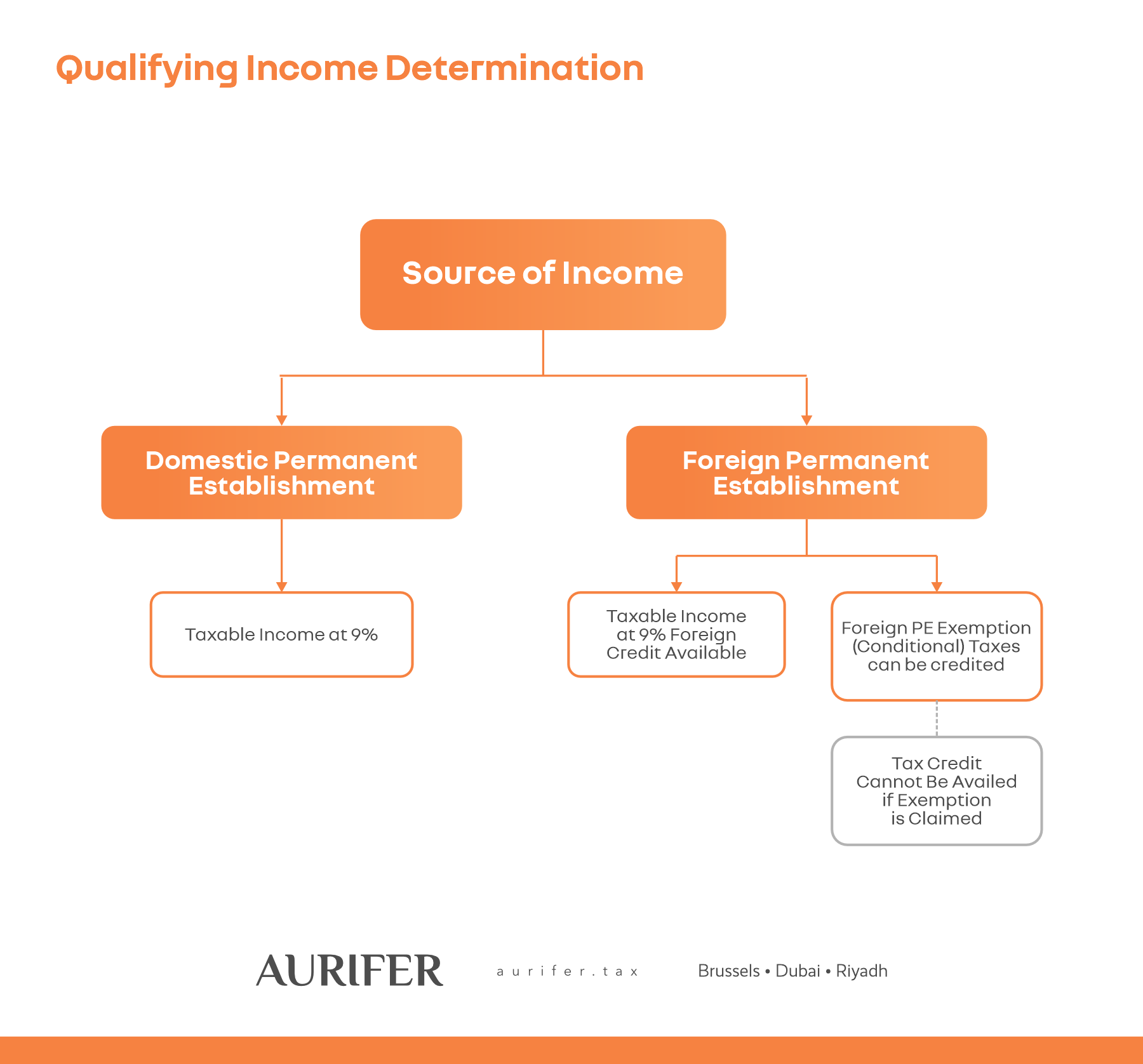

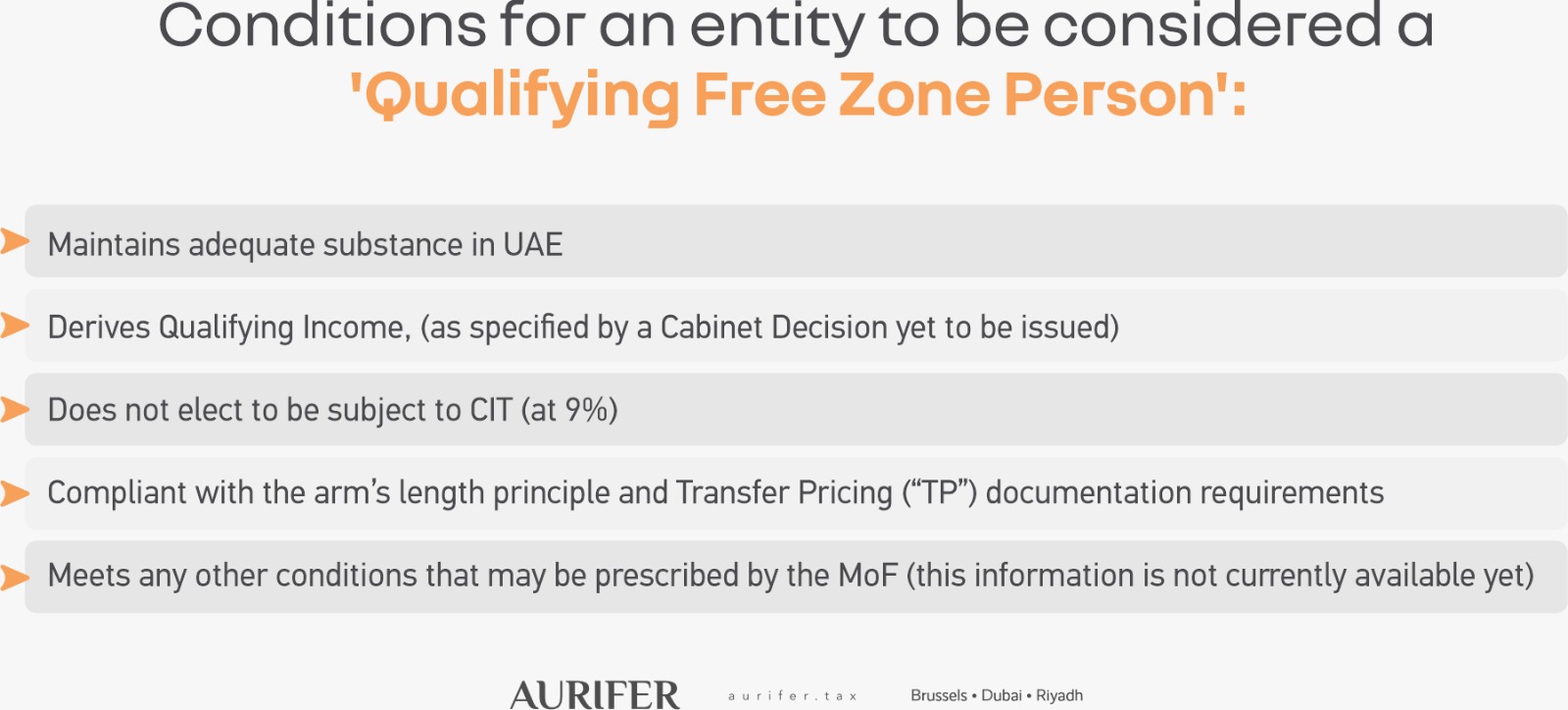

If none have unlimited liability, then the firm will be considered equivalent to an FZ LLC. Subsequently, the firm will need to analyze whether it earns qualifying income subject to 0%.

vi. Firm structured as a UAE FZ partnership

The first question which needs to be asked is whether the firm is transparent for tax purposes. The Company Regulations for the specific FZ will need to be analyzed to understand whether any of the partners have unlimited liability. In those FZs, different regimes may apply. For example, the DIFC has a separate limited partnership regime[29] , and so does the ADGM[30]. These regimes need to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.

If the partners have unlimited liability, then the firm will be considered tax-transparent. The levying of UAE CIT then moves to the partners’ level. Presumably, the partners will not be able to claim the status as a QFZP, since this is reserved for legal entities only, and, therefore, will be subject to tax at the standard UAE CIT rate of 9%.

vii. Firm structured as a UAE FZ branch of a foreign firm

The first question which again needs to be asked is whether the firm is transparent for tax purposes. The same criteria apply as for UAE mainland branches of a foreign firm.

If the branch is not transparent, the same complications may arise as to the allocation of profits to the branch. Given that it is established in an FZ, when not transparent, it will need to ask itself as well whether its income constitutes qualifying income.

viii. Summary Table

b. Other Considerations

i. Tax Grouping

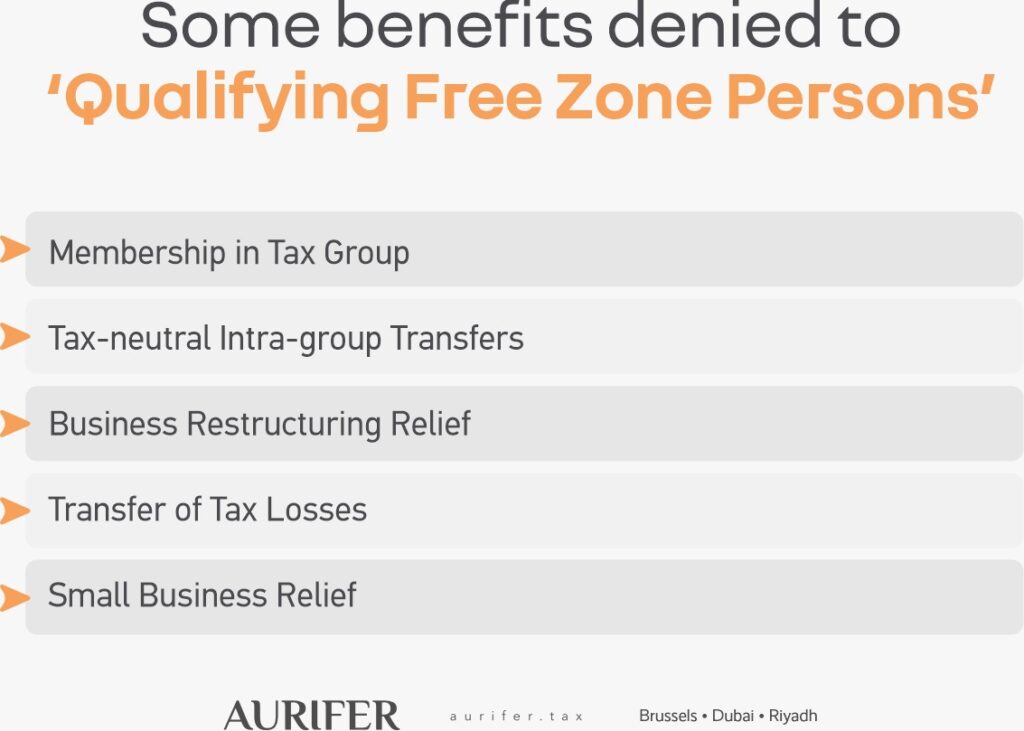

UAE companies are entitled to form a “fiscal unity” or Tax Group for UAE CIT purposes upon application before the FTA. The most important condition for a Tax Group to comply with is the (in)direct shareholding requirement of 95%. However, FZ entities whose qualifying income are subject to 0% cannot enter into a Tax Group. In addition, the parent (which can be intermediate) needs to be a UAE company. Under this arrangement, only one tax return needs to be filed[31]. These conditions also apply to partnerships or branches of foreign partnerships established in any of the UAE FZs.

The availability of Grouping would require that there are multiple legal entities in the UAE which are taxable persons under the same regime (i.e. the default regime where they are a taxable person)[32].

There are notable differences with VAT grouping, the most important of them likely being that the common shareholding percentage for VAT groups is 50% or more (whereas for tax groups it is 95% or more[33]), and for VAT groups Free Zone entities can be included, whereas Qualifying Free Zone Persons are excluded from entering a tax group[34].

Below is a comparative table comparing tax groups with VAT groups.

| Comparison | CIT | VAT |

| Consequence | Consolidation of profits and losses | Disregarding transactions between members VAT group considered as one taxable person for supplies and purchases and for right to recover input VAT |

| Common ownership | 95% share capital, voting rights and entitlement to profits | 50% voting/market value interest/control or side agreement Common Economic, financial and regulatory practices |

| Inclusion FZ/Exempt taxable persons | No | Yes |

| Transfer losses | Yes | N/A |

| Intra-group transfers | At no gain/no loss with 2 year claw back | Out of scope |

| Administration and payment | Parent | Responsible member |

| Joint liability | Yes – can be ring fenced on approval | Yes |

| Application | By parent and subsidiaries | By Responsible person |

2. Expenses of a law or professional services firm

a. Expenses of an LLC or a non-transparent partnership

There are no specific provisions applicable to the expenses incurred by a law or professional services firm. Therefore, expenses borne by both types of firms are subject to the general UAE CIT rules. However, certain matters are specific to UAE law firms and professional services firms, which may be relevant to consider. Those are:

– Deduction for UAE CIT purposes of paid remuneration

Employee’s remuneration, whether it is a base salary or other types of income allowances, constitutes a deductible expense for UAE CIT purposes. This holds true, irrespective of the nationality of the employee (i.e., UAE, GCC, non-UAE, and non-GCC). It might be assumed that pension and social security contributions, or GOSI contributions, for employees holding GCC nationality would also be deductible.

– End of Service Gratuity and Pension Contributions for Non-GCC nationals

Employees who do not hold GCC nationality and who are not employed by a DIFC company are subject to the EOS regime, where employers need to provision an amount which is a multiple of their base salaries.

Currently, the UAE legislation does not provide for any treatment of such EOS provisions or other provisions for that matter. In our view, however, provisions created for uncertain future payments, write-off of assets, etc. will most likely not be allowed a deduction under UAE CIT. However, provisions that are created for expenses that are actually crystallized/incurred may be allowed.

For contributions into Private Pension funds made by an employer on behalf of the employees, the total value of contributions is deductible[35]. However, the value of each Pension Plan Member cannot exceed 15% of the total Pension Plan Member’s remuneration, which gives entitlement to a deduction under UAE CIT[36]. We understand this provision to state that one single member cannot benefit from more than 15% of the benefits in the plan in order for the payments into the plan to be deductible[37].

We would normally expect DEWS, the DIFC Employee Workplace Savings Plan to qualify. However, if there are fewer than seven employees with equal contributions, the 15% condition will not be met , and therefore the amount of deductible contribution will be capped at 15%.

For employees of a Qualified Free Zone Person (QFZP), however, the tax deduction entitlement and limitation above may have no tax impact if the QFZP only has qualifying income, being that income taxed at a 0% rate. A tax impact would materialize if a QFZP also earns non-qualifying income.

– Bonuses

Bonuses are an important component of remuneration packages for fee earners and partners. Bonuses constitute the variable part of monthly or annual compensation, which depends on the monthly or annual financial performance of the law or professional services firm concerned. For fee earners and non-equity partners, those bonuses are usually granted as part of their remuneration package as employees. Bonuses are granted at the discretion of the management or constitute fixed bonuses (tiered or other), as referred to in the employment contract or in the employee manual.

For equity partners, several practices exist. In the UAE, so far, those practices have not been driven by any tax consideration. This explains why examples are known to us where equity partners in UAE firms received their profit share on a cash rather than accrual basis (e.g. 9 months after the end of the financial year to give sufficient time for clients to settle their bills).

Given that audit practices in the UAE were not always consistent, or even absent for some companies, there was less corporate governance, and practices have varied considerably.

Equity partners also often do not actually hold equity stakes. They are only referred to as equity partners in name but hold no shares in the company. They will often hold a right to profits or hold ghost equity. These are contractual rights to profits, rather than the legal right which a shareholder has to receive dividends distributed by a company in which he or she holds shares.

In other situations, partners may hold units, the value of which is, however, annually determined by the partnership’s management. Partners are awarded units, and once the profit pool is determined, the number of units held will determine the profits the partner is entitled.

Both in the cases of ghost equity and units, an important question will be whether this constitutes a deductible expense, or is equivalent to a dividend, and therefore is paid after tax (in which case the profits are higher and, therefore, the net tax liability of the company would be higher).

Given that these constitute rather a contractual right and not a right based on shares held in the entity, the revenues earned from these contractual rights would likely rather be a tax-deductible expense. Should this approach be correct, however, effective entitlement to a deduction under UAE CIT would require careful drafting of the partnership agreement upon a partner joining a partnership.

– Other employee-related expenses

Insurance such as the workmen’s compensation would likely be deductible. However, insurance paid by the employer on behalf of the employee, like the unemployment insurance scheme in place in the UAE, would likely not be deductible, as it is not an expense for which the employer is liable.

– The deduction for tax purposes of profits distribution for partners considered as “connected persons” and whether it is considered at a market rate

In order to be deductible for UAE CIT purposes, any payment or benefit granted to a “connected person” must correspond to the market value of what is provided by the connected person and is incurred wholly and exclusively for business purposes.

Connected persons are:

i. the owner of the taxable person,

The owner would be a natural person who directly or indirectly owns an ownership interest in the taxable person or controls the taxable person.

ii. a director or officer of the taxable person, or

iii. a related party of the first two categories.

UAE CIT further provides that partners in a transparent unincorporated partnership are considered connected persons, and so are any related parties of those partners[38].

To determine what is the applicable market value, UAE CIT legislation refers to transfer pricing principles. And yet, none of the transfer pricing methods referred to under the UAE CIT law lends itself to determining what a market rate remuneration for a partner’s salary is. Also, there is a considerable amount of variation between the more traditional courthouse lawyers on the one hand, and corporate or tax lawyers on the other.

For managing partners of a law firm who have a more ceremonial role, and actually do not feature on the trade license as managers, there should be no concern. Similarly, for managing partners who are managers on the license but have no different remuneration package as compared to their peers, there should be no impact.

Given also limited public information on partner remuneration, law and professional services firms may be confronted with complexities around defending partner remuneration for partners qualifying as connected persons.

– The deduction of entertainment expenses

UAE CIT law puts a 50% cap on any entertainment, amusement, or recreation expenditure incurred for the purposes of receiving and entertaining customers, shareholders, suppliers, or other business partners.

These expenditures include but are not limited to meals, accommodation, transportation, admission fees and facilities and equipment used in connection with entertainment. The MoF also has the possibility to determine other types of excluded expenditure.

Examples of this type of expenditure could be an iftar meal for clients, a reception for the opening of a new office in the presence of business partners, a shareholder meeting abroad in a tourist location, or a new year’s reception. In practice, the deductibility of such expenses may often be litigated and disputed by tax authorities[39].

Interestingly, the entertainment expenditure limitation does not seem to impact such expenses incurred for staff. We assume that this is subject to the general rule and therefore be limited by the requirement that this is a business expense.

– Expense reimbursements

Quite often, fee earners will incur expenses to be reimbursed (e.g., hotel, transportation, meals, translation fees, research in databases, etc.). In a professional services environment, those expenses are even more important. Also, these costs are often recharged to clients. When they are recharged, they constitute expenses for the firm, and revenue as well.

When expenses are incurred in the name and on behalf of the client (e.g., license fees, court fees, etc.), these costs do not run through the profit and loss account of the company but rather through the balance sheet. These costs are therefore not expenses nor revenues for the company. From a VAT point of view, these types of expenses will be disregarded from the taxable amount as well[40].

– The deductibility of interest payments

Law and professional services firms sometimes need to borrow money for a variety of reasons (e.g., expansion into new regions, fit out new office, etc.). An interest expense is a deductible expense for UAE CIT purposes.

However, UAE CIT legislation caps the deductibility of net interest expenditure at 30 % of EBITDA[41]. Net interest expenditure is the amount by which the interest expense (including interest expense rolled forward) exceeds the interest income.

By way of an example, if the revenues of a firm are AED 1,000 and its cost of sales and overhead expenses are AED 600, then its EBITDA is AED 400. Any interest expenses it may incur would only be deductible up to a value of AED 120 (i.e., 30% of AED 400).

The MoF has determined a safe harbour of AED 12 million, below which the 30% EBITDA cap does not apply[42]. When the net interest expense is capped, the balance between the cap and the actual net expense can be carried forward for a maximum of 10 years[43].

Any interest expense which would be disallowed under other provisions of UAE CIT law (e.g., because it relates to exempt dividends) is excluded from the net interest calculation[44].

Certain taxable persons are excluded from the 30% EBITDA cap, such as:

- Banks

- Insurance providers

- Natural Persons conducting a business, and

- Any other Person as determined by the MoF

Finally, a group cap may be available for consolidated businesses[45].

Specific financial assistance rules apply as well, disallowing interest expenses entirely in certain situations[46]. This is the case where a loan is obtained, directly or indirectly, from a related party, and it is obtained for specific purposes, which are:

- A divided or profit distribution to a related party

- A redemption, repurchase, reduction or return of share capital to a related party

- A capital contribution to a related party

- The acquisition of an ownership interest in a person who is or becomes a related party following the acquisition

The deduction is allowed nonetheless when it can be demonstrated that the main purpose of obtaining the loan is not to gain an advantage under UAE CT[47]. It is considered that there is no UAE CT advantage where the related party is subject to UAE CT (or a tax of a similar character) in the foreign jurisdiction on the interest at a rate not less than the standard rate of 9% under UAE CT.

– Donations to charitable organisations

Donations, gifts, and grants provided to Qualifying Public Benefit Entities in the UAE constitute a deductible expense[48].

Accordingly, taxable persons will be eligible to deduct an equivalent amount of such contributions for the purpose of calculating the corporate tax liability due for the period.

It should be noted that Qualifying Public Benefit Entities are exempt from UAE CIT, provided they meet the conditions laid down under Article 9 of the UAE CIT law[49].

Amongst others, the activity would need to be:

- Exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, artistic, cultural, athletic, educational, healthcare, environmental, humanitarian, animal protection or other similar purposes.

- As a professional entity, chamber of commerce, or a similar entity operated exclusively for the promotion of social welfare or public benefit.

Such Qualifying Public Benefit Entities may have an ancillary business activity, which may push those entities in the scope of VAT but allow them to be exempt from UAE CIT, nonetheless.

Any donations, gifts and grants provided to non-Qualifying Public Benefit Entities will not be deductible. That looks to be the case also when this happens in favor of a foreign entity[50].

The UAE’s Federal Cabinet has listed Qualifying Public Benefit Entities, including entities like universities, chambers of commerce, foundations, and charities, as well as professional, sport and cultural associations.[51].

b. Expenses of a transparent partnership or a transparent branch of a foreign partnership

Due to its transparency, the UAE transparent partnership or the transparent branch of a foreign partnership will have no tax liability themselves. Therefore, there are no meaningful considerations around tax-deductible expenses for those transparent entities.

For the avoidance of doubt as well, the provisions of UAE CIT law state that amounts which are withdrawn from a transparent unincorporated partnership by a natural person who is a taxable person are not deductible[52]. This likely is a reference to the transparent nature of such partnerships[53].

==

[END NOTES]

[1] FAQ #48, UAE Ministry of Finance Corporate Tax FAQs, https://mof.gov.ae/corporate-tax-faq/, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[2] UAE MoF’s Explanatory Guide on Federal Decree-law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Business, pp. 7 and 46, https://mof.gov.ae/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Explanatory-Guide-on-Federal-Decree-Law-No.47-of-2022-on-the-Taxation-of-Corporations-and-Businesses-2.pdf, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[3] Article 1 UAE CIT law.

[4] See Paragraph 8.3. of the OECD Commentary to the OECD MTC on Article 4, which states the following: “Where a State disregards a partnership for tax purposes and treats it as fiscally transparent, taxing the partners on their share of the partnership income, the partnership itself is not liable to tax and may not, therefore, be considered to be a resident of that State”. This reflects the idea of when a person is covered and is entitled to the benefit of a DTT as specified in Article 1(2) of the OEC MTC (as updated in 2017) as regards wholly or partly transparent entities. Some treaties will, however, specifically note that a partnership is a resident. See Article 4(1)(b) of the DTT between the United States and Luxembourg or Article 4(1) of the DTT between Belgium and Luxembourg

[5] Title 2 of Law No. 32 of 2021 (hereinafter, the UAE CC law).

[6] Article 39 of the UAE CC law.

[7] Article 62 of the UAE CC law.

[8] See MoF’s Explanatory Guide, p. 47, which reads as follows: “…for Corporate Tax purposes, the Unincorporated Partnership is treated as an aggregation of Persons whereby each Person (partner) is treated as carrying on, and being a part owner of, the Business and the assets and liabilities of the partnership in accordance with the contract underlying the Unincorporated Partnership”.

[9] Article 16, Clause 1 of the UAE CIT law.

[10] Article 16, Clause 10 of the UAE CIT law.

[11] Article 3, Clause 1 of Ministerial Decision No. 127 of 2023 on Unincorporated Partnership, Foreign Partnership and Family Foundation for the Purposes of the UAE CIT Law.

[12] Article 3, Clause 2 of Ministerial Decision No. 127 of 2023 on Unincorporated Partnership, Foreign Partnership and Family Foundation for the Purposes of the UAE CIT Law. Presumably, this applies only to equity rather than also salaried partners.

[13] OECD report on the attribution of profits to permanent establishments, 17 July 2008, https://www.oecd.org/tax/transfer-pricing/41031455.pdf, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[14] International tax implications for partnership are described at length in the OECD’s Partnership report, OECD (1999), The Application of the OECD Model Tax Convention to Partnerships, Issues in International Taxation, No. 6, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264173316-en, consulted on 30 June 2023, and also in OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project Neutralising the Effects of Hybrid Mismatch Arrangements Action 2: 2015 Final Report, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264241138-en.pdf?expires=1687676531&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=1A4EEFD494D5FA739D2503603BC67A97, pp. 139 – 143, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[15] See MoF’s Explanatory Guide, p. 47, which, in this regard, explains that “[t]he UAE applying a different tax treatment to a Foreign Partnerships that is treated as fiscally transparent in the relevant jurisdiction(s) could result in unintended and unwanted tax consequences, not only for the UAE resident partners in the Foreign Partnership, but also for any non-resident partners whose UAE tax position can be impacted as a result”.

[16] In this regard, see J. Jones, i.a., “Characterisation of Other States’ Partnerships for Income Tax”, Bulletin – Tax Treaty Monitor, Section 3.2, p. 306,

[17] Article 16, Clause 7(a) of the UAE CIT law.

[18] Article 16, Clause 7(b) of the UAE CIT law.

[19] Article 16, Clause 7(c) of the UAE CIT law and 4, Clause 1(a) of Ministerial Decision No. 127 of 2023 on Unincorporated Partnership, Foreign Partnership and Family Foundation for the Purposes of the UAE CIT Law.

[20] Article 16, Clause 7(c) of the UAE CIT law and Article 4, Clause 1(b) of Ministerial Decision No. 127 of 2023 on Unincorporated Partnership, Foreign Partnership and Family Foundation for the Purposes of the UAE CIT Law.

[21] Article 11, Clause 3(c) of the UAE CIT law.

[22] Comparing Article 1 of the UAE CIT law and Article 1 of the GCC VAT Agreement, the two definitions concerned match.

[23] Article 2, Clause 1(a) of Cabinet Decision No. 49 of 2023.

[24] Ultimately, the outcome will much depend on the approach of the country of residence/formation of the partnership towards CIT paid in the UAE as the country of source of the income, and how potentially international double taxation between the two countries may be avoided.

[25] Article 4, Clause 2 of Ministerial Decision No. 127 of 2023 on Unincorporated Partnership, Foreign Partnership and Family Foundation for the Purposes of the UAE CIT Law.

[26] Agreement between the Government of the United Arab Emirates and the Government of the United States of America to improve International Tax Compliance and to Implement FATCA of 17 June 2015, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/FATCA-Agreement-UAE-6-17-2015.pdf, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[27] See the DIFC’s Limited Partnership Law No 4 of 2006, https://www.difc.ae/business/laws-regulations/legal-database/limited-partnership-law-difc-law-no-4-2006/, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[28] See the ADGM’s Limited Liability Partnership’s Regulations, https://en.adgm.thomsonreuters.com/rulebook/limited-liability-partnerships-regulations, consulted on 30 June 2023.

[29] See the DIFC’s Limited Partnership Law No 4 of 2006, https://www.difc.ae/business/laws-regulations/legal-database/limited-partnership-law-difc-law-no-4-2006/.

[30] See the ADGM’s Limited Liability Partnership’s Regulations, https://en.adgm.thomsonreuters.com/rulebook/limited-liability-partnerships-regulations.

[31] Article 40 of the UAE CIT law states on Tax Groups the following:

- A Resident Person, which for the purposes of this Decree-Law shall be referred to as a “Parent Company”, can make an application to the Authority to form a Tax Group with one or more other Resident Persons, each referred to as a “Subsidiary” for the purposes of this Chapter, where all of the following conditions are met:

- a) The Resident Persons are juridical persons.

- b) The Parent Company owns at least 95% (ninety-five percent) of the share capital of the Subsidiary, either directly or indirectly through one or more Subsidiaries.

- c) The Parent Company holds at least 95% (ninety-five percent) of the voting rights in the Subsidiary, either directly or indirectly through one or more Subsidiaries.

- d) The Parent Company is entitled to at least 95% (ninety-five percent) of the Subsidiary’s profits and net assets, either directly or indirectly through one or more Subsidiaries.

- e) Neither the Parent Company nor the Subsidiary is an Exempt Person.

- f) Neither the Parent Company nor the Subsidiary is a Qualifying Free Zone Person.

- g) The Parent Company and the Subsidiary have the same Financial Year.

- h) Both the Parent Company and the Subsidiary prepare their financial statements using the same accounting standards.

[32] Article 40 of the UAE CIT Law.

[33] Article 40, 1, b of the UAE CIT Law.

[34] Article 40, 1, f of the UAE CIT Law.

[35] Article 5, Clause 1 of Ministerial Decision No. 115 of 2023 on Private Pension Funds and Private Social Security Funds for Corporate Tax Purposes

[36] Article 5, Clause 3 of Ministerial Decision No. 115 of 2023 on Private Pension Funds and Private Social Security Funds for Corporate Tax Purposes

[37] The 15% contribution cap likely is meant to avoid opportunistic behaviors by employers which might try to inflate some employees’ (perhaps those with managing positions) pension plan contributions.

[38] Article 36, Clause 4 of the UAE CIT law.

[39] The same applies for UAE VAT purposes. See, in particular, the Taxable Person Guide for Value Added Tax (June 2018), pp. 39-40, which states the following: “A business is generally prohibited from recovering input tax on expenses incurred in respect of the provision of entertainment to anyone not employed by the business, including customers, potential customers, officials, shareholders, owners, and investors in the business. The type of entertainment expenses which are covered by the restriction include hospitality (e.g..accommodation, food and drinks) which are not provided in the normal course of a meeting, access to shows or events, or trips provided for the purposes of pleasure or entertainment. This means that where a business incurs any such expenses, the business will not be able to recover VAT incurred on the expenses”.

[40] See Article 26, Clause 6(c) of the GCC VAT Agreement, which excludes from the VAT taxable amount “c) amounts paid by the Taxable Supplier in the name of and to the account of the Customer. In this case, the Taxable Supplier may not deduct Tax paid on these expenses”.

[41] EBITDA stands for “Earnings Before Interest Tax Depreciation and Amortization”.

[42] Article 30, Clause 3 of the UAE CIT law and article 8 of Ministerial Decision No. 126 of 2023 on the General Interest Deduction Limitation Rule for the UAE CIT law.

[43] Article 30, Clause 4 of the UAE CIT law.

[44] Article 30, Clause 5 of the UAE CIT law.

[45] Article 30, Clause 7 of the UAE CIT law.

[46] Article 31, Clause 1 of the UAE CIT law.

[47] Article 31, Clause 2 of the UAE CIT law.

[48] A contrario, Article 33, Clause 1 of the UAE CIT law.

[49] These are further detailed in Cabinet Decision No. 37 of 2023.

[50] This may fall foul of the non-discrimination provisions in the GCC Economic Agreement of 2001, more specifically Article 3, Clause 1.

[51] Cabinet Decision No. 37 of 2023 Regarding the Qualifying Public Benefit Entities for the Purposes of Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 on the Taxation of Corporations and Businesses.

[52] Article 33, Clause 5 of the UAE CIT law.

[53] A contrario, a combination of non-deductibility of the expenses in the hands of the non-transparent unincorporated partnership and taxation in the hands of the natural person receiving the income would lead to double taxation.