Menu

Year end checklist

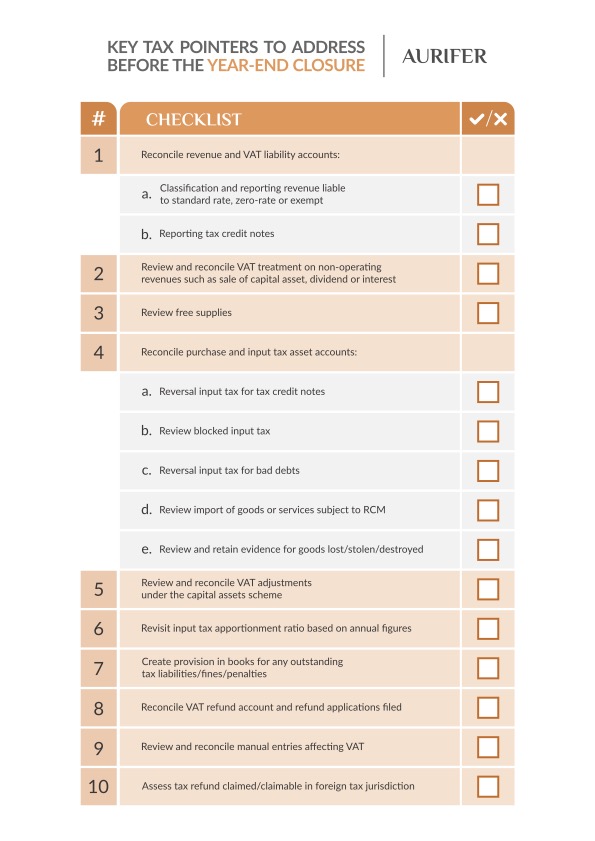

This is Aurifer's year end checklist with key tax pointers to address before year end closure.

The UAE is aspiring to become a leader in the cryptocurrency business in the region and it is aiming to attract more than 1,000 cryptocurrency businesses in 2022. To position itself against the regional and global competition, it has recently developed an advanced regulatory framework. Both central, on-shore authorities such as the Central Bank of UAE (“CB”) and Securities and Commodities Authority (“SCA”), and some of the free-zones, such as DIFC, ADGM and the DMCC have enacted advanced legal frameworks, while DWTC has announced an important partnership with a Crypto Exchange. It is expected that DWTC will also implement a comprehensive regulatory framework.

While the regulatory environment is quite advanced for this part of the world, the tax framework in the UAE is still relatively immature. In light of the UAE VAT law, it will be interesting to see how the Federal Tax Authority will take position vis-a-vis different transactions involving cryptocurrencies, crypto assets, and related services (wallets, brokerage, decentralised finance). Furthermore, in light of the potential introduction of Corporate Income Tax in the UAE as a consequence of the Global BEPS 2.0 initiative, it would be interesting to see the position of the UAE authorities taken towards taxation of the crypto space.

The authors aim to answer some of these questions, from the viewpoint of different possible taxes. This article does not aim to be comprehensive, nor explain how blockchain works.

The article has a focus solely on the UAE’s tax and regulatory framework, as it constitutes at least the most ambitious jurisdiction in the region, intending to stimulate the development of a crypto sector in the UAE. Other jurisdictions, such as Bahrain, have also enabled exchanges to establish themselves there. Bahrain has a relatively comparable tax framework to the UAE. The other GCC countries are largely absent in the field.

We will not be covering the Emirate Banking Tax Decrees nor the General Tax Decrees in the Emirates, which constitute taxation on a local (i.e. Emirate) level.

The framework is fast paced and subject to fast evolution, as adoption spreads. It is also shaky, with Tesla accepting and then again denying cryptocurrencies as payment for its cars, and China cracking down on crypto.

Regulatory Context

The Regulatory Framework in the UAE which could impact crypto is determined on the one hand for mainland companies by the Securities and Commodities Authority (SCA) and the Central Bank (CB), and on the other hand by the Federal Financial Free Zone Authorities established in the Dubai International Financial Center, and the Abu Dhabi Global Markets.

In on-shore UAE, the CB and the SCA share responsibility for the regulatory oversight of the UAE’s financial and capital markets. This includes the non-financial free zones, such as the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC) and Dubai World Trade Center (DWTC). On the other hand, financial free zones, i.e. ADGM and DIFC have provided their separate regulatory framework for the entities established within their jurisdictions.

From the on-shore side of regulation, the CB has regulated crypto assets and included digital tokens (such as digital currencies, utility tokens or asset-backed tokens) and any other virtual commodities,[1] While the CB maintains that crypto-assets are not legal tender, the CB explicitly allows crypto-assets to be used as a stored value when purchasing other goods and services.

The SCA framework[2] applies generally to SCA regulated “Financial Activities” in respect of crypto-assets in the UAE, which include promotion and marketing, issuance and distribution, advice, brokerage, custody and safekeeping, fundraising and operating an exchange of crypto assets.

The DIFC freezone regulates only “Investment Tokens” which are basically securities or derivatives based on the blockchain technology. This means that key cryptocurrencies, as well as stablecoins, will remain unregulated under the Investment Tokens regime.

The ADGM freezone issued the most advanced and comprehensive framework regulating the operation of crypto-asset businesses. It has regulated virtual assets (such as non-fiat virtual currencies), digital securities, fiat tokens (i.e. stablecoins), and derivatives and funds (i.e., derivatives over any digital assets and collective investment funds investing in digital assets) while other crypto assets remain unregulated. From a regulatory policy perspective, the FSRA treats virtual assets as commodities. Even though not all virtual assets are specified investments, any market operator, intermediary or custodian is required to be approved by ADGM as a financial service permission holder in relation to the applicable regulated activity.[3]

One topic that has not been regulated both on-shore and in the free zones is the growing DeFi industry, which is becoming central to the blockchain and crypto space globally. There are no incentives for permissionless peer-to-peer systems and DeFi to develop. It remains to be seen whether this stance will change in the near future, and hence we will not analyse the tax consequences in the DeFi industry. A further area of uncertainty is the status of NFTs as they remain undefined.

DeFI, Investment Tokens (digital securities), and utility tokens asset based tokens are not further discussed in this article.

The VAT conundrum – Out of scope as money, or a service?

The mining, exchange or disposal of cryptocurrencies, as well as other transactions occurring in the crypto industry may have VAT consequences. Hence, the definition of the crypto-assets and related services is particularly important in determining their VAT treatment. VAT is a consumption tax with a wide scope, and therefore it is imaginable that some transactions may be subject to VAT.

In contrast with income taxation, where the accounting treatment is usually followed directly, with some adjustments, in the comparative VAT practice, cryptocurrencies are often treated as akin to fiat currencies in the VAT treatment of transactions involving their exchange or disposal.

Regulatory definitions and the framework can give some guidance when interpreting the potential VAT treatment of different types of crypto-assets and the related services. There is a relatively broad similarity among EU countries as to the VAT treatment for transactions involving cryptocurrencies. There is greater divergence among countries comparatively in the treatment of “related” or “back-office” services, such as custodial services, online wallet services and exchange services.

GCC and UAE VAT for Financial Services

The Gulf Cooperation Council’s VAT Agreement of 2016 was based on the EU VAT directive in a version after 2011 but before 2013. However, for the Financial Sector, it allowed significant leeway to implement local policies. Article 36 of the GCC VAT Agreement prescribes that financial services provided by licensed banks and financial institutions are exempt from VAT. It further allows that Member States apply fixed refund rates for financial institutions (with inspiration drawn from Singapore), and in its second paragraph allows full freedom to apply “any other tax treatment”.

In the Financial Services sector, the UAE and the Gulf Cooperation Council have deviated significantly from the European VAT directive, which do not grant the same liberty in terms of setting tax policy to its Member States.

When the UAE and KSA issued their laws in 2017, and with KSA being the first, they had prescribed a system where financial services where the provider makes money on the basis of a spread are VAT exempt (see here for our article on VAT exempt persons: https://www.aurifer.tax/news/special-tax-payers-in-the-gcc-exempt-taxable-persons/?lid=438), and where these are fee-based, they are taxed. Since then Bahrain in 2019, and Oman on 16 April 2021, have not deviated from their predecessors.

Far clearer than the VAT regimes applicable to financial services in Europe, given that the scope is narrower, it also entails more services are subject to VAT. This is a double edged sword, as the input recovery increases, but also the cost for customers that do not recover input VAT.

The VAT laws in the UAE and the GCC focus on more traditional banking services, and do not discuss the novelties which are the subject of this article. Neither do the laws in the rest of the world for that matter. That is not surprising, as the VAT laws are general set of rules, intended to apply widely on a large number of situations.

In the UAE, the UAE VAT law in article 46, 1 simply refers to financial services as being exempt from VAT and relies on the UAE VAT Executive Regulations. Article 42, 2 of the UAE VAT Executive Regulations then refers to “services connected to dealings in money (or its equivalent)”. The same article then goes on the list a number of services by way of illustration which would constitute such exempt financial services. None of these services listed link directly to cryptocurrencies.

The only principle to go by, is that the UAE’s FTA states that “the starting point for the UAE VAT treatment is that VAT should be charged on financial services where it is practicable to do so”. This is however not easy to implement, and may even seem at odds with the exemption for interest on loans, since it may be practicable to add VAT to interest.

Tax authorities are usually late to the game with this type of novelties, and therefore the GCC are no different. However, given that the UAE wants to position itself on the matter, it may be good if it considered a clear position. We have therefore analysed below a number of typical transactions involving crypto and their applicable VAT regime.

It is to be noted, that even in the carved out Federal Financial Free Zones, in terms of taxation, currently in the UAE, no exceptions apply to the general regime.

Starting with mining crypto

There is a relatively broad consensus among countries as to the VAT treatment for transactions involving the mining of virtual currencies. The mining of virtual currencies is their creation through mining activities. The person mining the currency therefore acquires assets in the process of mining.

There is no public position from the UAE’s Federal Tax Authority on the matter, but it may draw inspiration from research conducted by the OECD (OECD (2020), Taxing Virtual Currencies: An Overview Of Tax Treatments And Emerging Tax Policy Issues, OECD, Paris. www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/taxing-virtual-currencies-an-overview-of-tax-treatments-and-emerging- tax-policy issues.htm).

In that research, the OECD cites an EU VAT Committee report (an advisory body with no legal power; you can find the VAT Commitee’s Working Paper 854 on Bitcoin here), which found that mining activities should be out of scope of VAT.

This is largely attributed to the fact that there is no direct link between the remuneration of the mining and the activity itself.

The possible alternative qualification in the EU is that mining constitutes a service related to currency, and is therefore exempt from VAT.

Small jurisdictions which exempt the mining of cryptocurrencies domestically but allow it to be zero rated when dealing with foreign customers, could offer substantial advantages, since the zero rate would allow the sellers to recover the input VAT. This may be a potential tax policy option for the UAE or Bahrain.

As Bitcoin reaches its capped supply, and there will be no more mining, its economics will alter. The incentives for various members in its ecosystem, such as miners and traders, will change. For example, miners may rely less on block rewards and more on transaction fees to earn revenue and profits for their operations. Those transaction fees might be regarded as taxable financial services in the UAE.

If it is considered that mining is in scope of VAT, which we are not advocating, unless it would be VAT exempt, the multitude of actors may still see different VAT regimes applicable, since some of the smaller miners may not reach the mandatory registration threshold.

Holding crypto

The holding of cryptocurrency as such should be equated to holding on to an asset. From a VAT point of view, since it is a transaction tax and holding it involves no transaction, there should be no impact. That holds true as well even if the currency appreciates or depreciates in value.

Selling and buying crypto

The main discussion therefore evolves around whether the sale and purchase of a crypto currency is a service (and therefore constitutes a barter transaction), or should be considered as the equivalent of using and purchasing money.

In the EU, to exempt financial services from VAT, and also money services, the VAT directive states that the EU Member States shall exempt “transactions, including negotiation, concerning currency, bank notes and coins used as legal tender” (article 135, 1, e Recast EU VAT Directive 2006/112/EC).

The European Court of Justice (C-264/14, Hedqvist) had judged that the exchange of legal tender against bitcoin, a cryptocurrency, is a service, and an exempt one at that. Bitcoins are treated as akin to fiat currencies (i.e. traditional currencies).

While the definitions in the GCC are different, and while above we had discussed that the GCC Agreement allows for much more tax policy room than the EU VAT Directive, the guidance clearly points towards the concepts in the EU. The ECJ ruling therefore does not constitute a source of law, but is definitely an authority on the matter.

The ruling is potentially subject to challenges, and not all authors would agree with the position taken. The ECJ only ruled on bitcoins, however the reasoning can be applied to similar cryptocurrencies which function in the same way.

Especially the comparison with legal tender in terms of its functionality can be flawed, as not all cryptocurrencies are accepted for payment purposes.

When considering the sale of cryptocurrency as in scope of VAT and exempt, small jurisdictions which allow the trading of cryptocurrencies to be zero rated when dealing with foreign customers, could offer substantial advantages, since the zero rate would allow the sellers to recover the input VAT.

In the authors’ modest opinion, for the sale and purchase of crypto itself, it can be broadly considered as the equivalent of fiat currency for the purpose of VAT treatment, and therefore should be considered as out of scope of VAT.

Using crypto to acquire goods or services

Considering that the SVF Regulation of the Central Bank allows crypto-assets to be used as a stored value when purchasing other goods and services, it is an argument in favor that it could be regarded as an equivalent of using the fiat currencies, and therefore using it to acquire goods or services should not entail any VAT consequences, in the same way as one would use fiat currency to purchase a good or service.

The supply of goods and services, subject to VAT and remunerated by way of Bitcoin, for example, would for VAT purposes be treated in the same way as any other supply. VAT should therefore be levied on the value of the goods or services provided.

However, if UAE would consider that the buyer is rendering a service by paying with cryptocurrencies, the transaction will constitute a barter, and is therefore taxable because of the sale of the good or service, and is taxable on the value of the cryptocurrency handed over to the seller.

There are a number of technical complexities associated with such a barter, such as the valuation and the use of an exchange rate, but to avoid complexities it would be better to stay consistent with considering cryptocurrency like a traditional currency, considering that treating the use of crypto to acquire goods or services as bartering would lead to an awkward result.

Crypto brokerage and wallet providers

As for crypto intermediation services – services related to crypto exchange, brokerage, and wallet/custodial servicesproviders, the question is would it be qualified simply as services or would it fall under financial services.

As for the crypto exchanges and brokerages, even though the EU VAT Committee has taken a position that their services should be taxable, in practice EU countries (such as Germany, France and Italy) are exempting their services from VAT, following the ECJ decision in Heqvist. The same approach is taken in the UK where these services are exempt in line with the treatment of the financial services.

An argument to consider these services as financial services is that their activities are regulated by the SCA regulation and that they are specifically referred to as Financial activities in the Crypto Assets Regulations Explanatory Guide issued by the SCA.

However, given the GCC VAT specifics and the different structure of the fees charged to the customers, crypto exchanges might be exempt on the spreads/margins made while any flat fees/ fixed fees might be taxable, except if the customer is based abroad where such services would be zero rated with a possibility of a deduction. Finally as there are different types of traders and exchanges (centralized / decentralized, principal trading / brokerage trading) the analysis of their fees, agency arrangements and taxation should be further analysed and may be complex.

However, given the UAE’s goal to give a competitive advantage to the crypto businesses set up locally compared to other jurisdictions, it should be taken into account that VAT would be putting the consumers in UAE at a disadvantage compared to other consumers globally, who can buy and sell cryptocurrencies without VAT. Furthermore, it would harm the competitiveness of the local UAE based exchanges against the exchanges abroad.

Finally, the UAE should take into account that VAT exemption in other jurisdictions was also based on the fact that taxing each and every transaction would lead to disproportionate administrative burden given the volatility of crypto prices and the amount of trades and transactions concluded on a daily basis.

On the side of wallet / custodial services, there are different types of wallets and related services – the so called “hot” (software based) or “cold” (hardware based) wallets, or arranging for third party storage of private keys. Service providers might or might not charge a fee for the provision of such services, as these services might be provided standalone or related to other, main services (sale and purchase of cryptocurrency or trading services and similar). There are different approaches in taxing these fees comparatively, and some countries exempt those fees on the grounds that these services are closely linked to the main, exempt service or tax them as a separate – non financial service. In the UAE, the situation is much clearer and such wallet or custodial services are simply standard rates.

Other indirect taxes

While at first sight, there would be no other indirect taxes applicable, potentially real estate transfer taxes would come into sight with tokenisation of real estate – i.e. the asset backed tokens. Although set at a different level, and not a direct property right or a right in rem, anti-avoidance rules may trigger the application of transfer duties nonetheless.

Not subject to Personal Income Tax

Contrary to the discussions one may have in other jurisdictions as to the categorization of the gains of the sale of crypto for tax purposes, given the absence of personal income tax in the GCC, the discussion whether the gains constitute professional income, trading income, speculative income, income from capital or other taxable income, does not play.

However, one could imagine that tax authorities which have corporate tax systems may want to be tempted to consider the income as business income and tax it.

Equally so, for the same reason, the creation or mining of cryptocurrency would not lead to taxation under personal income tax in the UAE, or the wider GCC.

As a comparison, reportedly in the US, the creation of bitcoins through mining needs to be included at the fair market value of the virtual currency in gross income at the date of receipt. If the taxpayer is conducting a trade or a business, the taxpayer is considered self-employed.

The planned introduction of Personal Income Tax for high earners in Oman in 2023 may see the first discussions around the topic.

Transfer pricing complexity and potential CIT treatment.

The UAE only has a fairly light transfer pricing (“TP”) framework, with no requirements for master files or local files, and only the requirement for an Ultimate Parent Entity to file a Country by Country Report (Cabinet Resolution No. 44 of 2020).

This may very soon change, with the implementation of BEPS 2.0, which may entail significant changes to the UAE’s tax regime, where we can potentially expect some form of Corporate Tax together with a Transfer Pricing regime.

Even though the UAE has a fairly light transfer pricing framework, it is by nature a very international jurisdiction, and therefore it is common for UAE businesses to have voluntarily adopted a transfer pricing framework applicable to the UAE.

Two interesting aspects of TP of the crypto universe are the intercompany transactions done in crypto and the intercompany transactions of the international groups involved in the crypto industry.

Given that some of the large investment funds and other companies are now investing in crypto as an asset or a hedging mechanism against inflation, and that the cryptocurrencies could facilitate cross border payments, it is reasonable to expect that, as the cryptocurrency adoption increases, multinational corporate groups could hold cryptocurrencies and transfer them within the group in exchange for fiat currencies or other goods and services.

How would the TP methodology apply to such types of transactions? The First option is to perform the analysis at the level of profitability of the involved entities based on their functional analysis and the Group’s value chain. Conversely, pure cryptocurrency transactions that cannot be justified with profit based methods would need to rely on CUPs (Comparable Uncontrolled Prices) where accurate valuation of the crypto assets at the moment of a transaction would be a key issue.

Given the volatility of the cryptocurrency prices (excluding the stablecoins), the traditional benchmarking ranges might not be precise enough. Yet, in case of a high volume of transactions, tracking each and every transaction and comparing the prices at the date of the transaction would lead to a significant administrative burden in documenting the intercompany transactions. Furthermore, such prices could not be compared directly with the market prices as they would have to be discounted or increased for various intermediary fees, to reflect the arm’s length conditions. This will present a challenge for Transfer pricing practitioners and benchmarking software providers as well as an opportunity to potentially solve this matter with some new software benchmarking solutions and adjustments that could allow for accurate CUP benchmarking.

Cryptocurrency related businesses such as crypto exchanges, traders, brokerages, crypto advisors, custody (wallet) providers, marketing and other ancillary services providers, which will be still be in between different growth stages from a start up to a larger multinational would have a different set of TP issues on their side. We can expect to see a value chain that combines the elements of a technology/IT based business, commodity trading business and typical back office and marketing support businesses. The value chains would largely revolve around key technologies employed, company branding and distinctive products/services offerings as the key high value adding drivers. Following the usual TP methodology, the key would be ensuring that these functions are appropriately remunerated with higher margins and/or appropriate residual profits. Given that many crypto businesses would enter the UAE market, we can expect their regional HQs to be subject to scrutiny on their transfer pricing arrangements in other jurisdictions in the region given the rapidly evolving TP landscape in the Middle East as well as the BEPS 2.0 developments that are targeting the large international businesses based in low tax jurisdictions.

Finally, if UAE indeed takes a leap into CIT as a consequence of the BEPS 2.0, it is important to note that CIT typically follows the accounting treatment. IFRS IC has classified holding cryptocurrencies as intangible assets (rejecting the qualification of financial assets or cash), unless they are held for sale in the ordinary course of business, in which case cryptocurrencies would be treated as inventories. In case of a longer holding period, the gains / losses realised should be treated as capital gains while in cases of shorter holding periods and therefore purchases and sales at the level of inventory, the gains/losses should be taxed as ordinary business income. Valuation of these assets is another matter that should be sorted by the IFRS or the separate guidance of the corporate income tax law.

A few other novel topics come to mind such as Permanent Establishment risks for overseas traders, Withholding tax implications for technology and financially based cross border transactions, but we can only expect that tax implications will largely lag behind the industry developments. It is fair to say that much can and still will be said, and that further technological developments will challenge the tax framework.

Milos Krstic – Head of Tax at Rain, the first Middle East crypto brokerage

Thomas Vanhee – Tax Partner, Aurifer

[1] UAE Central Bank, Stored Value Facilities (SVF) Regulation, available at https://centralbank.ae/sites/default/files/2020-11/Stored%20Value%20Facilities%20%28SVF%29%20Regulation%20AR%20%26%20EN.pdf

[2] https://www.sca.gov.ae/en/regulations/regulations-listing.aspx#page=1

[3] https://thelawreviews.co.uk/title/the-virtual-currency-regulation-review/united-arab-emirates

© Aurifer

Developed By Volga Tigris Digital Marketing Agency